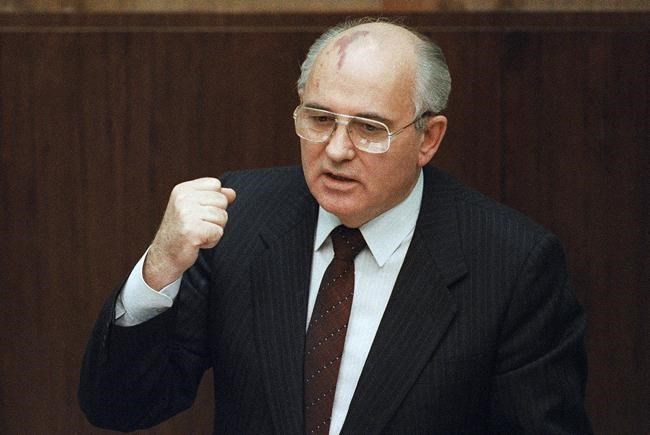

MOSCOW (AP) — Mikhail Gorbachev, who set out to revitalize the Soviet Union but ended up unleashing forces that led to the collapse of communism, the breakup of the state and the end of the Cold War, died Tuesday. The last Soviet leader was 91.

Gorbachev died after a long illness, according to a statement issued by the Central Clinical Hospital in Moscow. No other details were given.

Though in power less than seven years, Gorbachev unleashed a breathtaking series of changes. But they quickly overtook him and resulted in the collapse of the authoritarian Soviet state, the freeing of Eastern European nations from Russian domination and the end of decades of East-West nuclear confrontation.

“Hard to think of a single person who altered the course of history more in a positive direction" than Gorbachev, said Michael McFaul, a political analyst and former U.S. ambassador in Moscow, on Twitter. “Gorbachev was an idealist who believed in the power of ideas and individuals. We should learn from his legacy.”

Gorbachev's decline was humiliating. His power hopelessly sapped by an attempted coup against him in August 1991, he spent his last months in office watching republic after republic declare independence until he resigned on Dec. 25, 1991. The Soviet Union wrote itself into oblivion a day later.

A quarter-century after the collapse, Gorbachev told The Associated Press that he had not considered using widespread force to try to keep the USSR together because he feared chaos in the nuclear country.

“The country was loaded to the brim with weapons. And it would have immediately pushed the country into a civil war,” he said.

Many of the changes, including the Soviet breakup, bore no resemblance to the transformation that Gorbachev had envisioned when he became Soviet leader in March 1985.

By the end of his rule, he was powerless to halt the whirlwind he had sown. Yet Gorbachev may have had a greater impact on the second half of the 20th century than any other political figure.

“I see myself as a man who started the reforms that were necessary for the country and for Europe and the world,” Gorbachev told the AP in a 1992 interview shortly after he left office.

“I am often asked, would I have started it all again if I had to repeat it? Yes, indeed. And with more persistence and determination,” he said.

Gorbachev won the 1990 Nobel Peace Prize for his role in ending the Cold War and spent his later years collecting accolades and awards from all corners of the world. Yet he was widely despised at home.

Russians blamed him for the 1991 implosion of the Soviet Union — a once-fearsome superpower whose territory fractured into 15 separate nations. His former allies deserted him and made him a scapegoat for the country’s troubles.

His run for president in 1996 was a national joke, and he polled less than 1% of the vote.

In 1997, he resorted to making a TV ad for Pizza Hut to earn money for his charitable foundation.

“In the ad, he should take a pizza, divide it into 15 slices like he divided up our country, and then show how to put it back together again,” quipped Anatoly Lukyanov, a one-time Gorbachev supporter.

Gorbachev never set out to dismantle the Soviet system. What he wanted to do was improve it.

Soon after taking power, Gorbachev began a campaign to end his country’s economic and political stagnation, using “glasnost,” or openness, to help achieve his goal of “perestroika,” or restructuring.

In his memoirs, he said he had long been frustrated that in a country with immense natural resources, tens of millions were living in poverty.

“Our society was stifled in the grip of a bureaucratic command system,” Gorbachev wrote. “Doomed to serve ideology and bear the heavy burden of the arms race, it was strained to the utmost.”

Once he began, one move led to another: He freed political prisoners, allowed open debate and multi-candidate elections, gave his countrymen freedom to travel, halted religious oppression, reduced nuclear arsenals, established closer ties with the West and did not resist the fall of Communist regimes in Eastern European satellite states.

But the forces he unleashed quickly escaped his control.

Long-suppressed ethnic tensions flared, sparking wars and unrest in trouble spots such as the southern Caucasus region. Strikes and labor unrest followed price increases and shortages of consumer goods.

In one of the low points of his tenure, Gorbachev sanctioned a crackdown on the restive Baltic republics in early 1991.

The violence turned many intellectuals and reformers against him. Competitive elections also produced a new crop of populist politicians who challenged Gorbachev’s policies and authority.

Chief among them was his former protege and eventual nemesis, Boris Yeltsin, who became Russia’s first president.

“The process of renovating this country and bringing about fundamental changes in the international community proved to be much more complex than originally anticipated,” Gorbachev told the nation as he stepped down.

“However, let us acknowledge what has been achieved so far. Society has acquired freedom; it has been freed politically and spiritually. And this is the most important achievement, which we have not fully come to grips with in part because we still have not learned how to use our freedom.”

There was little in Gorbachev’s childhood to hint at the pivotal role he would play on the world stage. On many levels, he had a typical Soviet upbringing in a typical Russian village. But it was a childhood blessed with unusual strokes of good fortune.

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev was born March 2, 1931, in the village of Privolnoye in southern Russia. Both of his grandfathers were peasants, collective farm chairmen and members of the Communist Party, as was his father.

Despite stellar party credentials, Gorbachev’s family did not emerge unscathed from the terror unleashed by Soviet dictator Josef Stalin: Both grandfathers were arrested and imprisoned for allegedly anti-Soviet activities.

But, rare in that period, both were eventually freed. In 1941, when Gorbachev was 10, his father went off to war, along with most of the other men from Privolnoye.

Meanwhile, the Nazis pushed across the western steppes in their blitzkrieg against the Soviet Union; they occupied Privolnoye for five months.

When the war was over, young Gorbachev was one of the few village boys whose father returned. By age 15, Gorbachev was helping his father drive a combine harvester after school and during the region’s blistering, dusty summers.

His performance earned him the order of the Red Banner of Labor, an unusual distinction for a 17-year-old. That prize and the party background of his parents helped him land admission in 1950 to the country’s top university, Moscow State.

There, he met his wife, Raisa Maximovna Titorenko, and joined the Communist Party. The award and his family’s credentials also helped him overcome the disgrace of his grandfathers’ arrests, which were overlooked in light of his exemplary Communist conduct.

In his memoirs, Gorbachev described himself as something of a maverick as he advanced through the party ranks, sometimes bursting out with criticism of the Soviet system and its leaders.

His early career coincided with the “thaw” begun by Nikita Khrushchev. As a young communist propaganda official, he was tasked with explaining the 20th Party Congress that revealed Soviet dictator Josef Stalin’s repression of millions to local party activists. He said he was met first by “deathly silence,” then disbelief.

“They said: ‘We don’t believe it. It can’t be. You want to blame everything on Stalin now that he’s dead,’” he told the AP in a 2006 interview.

He was a true if unorthodox believer in socialism. He was elected to the powerful party Central Committee in 1971, took over Soviet agricultural policy in 1978 and became a full Politburo member in 1980.

Along the way, he was able to travel to the West, to Belgium, Germany, France, Italy and Canada. Those trips had a profound effect on his thinking, shaking his belief in the superiority of Soviet-style socialism.

“The question haunted me: Why was the standard of living in our country lower than in other developed countries?” he recalled in his memoirs. “It seemed that our aged leaders were not especially worried about our undeniably lower living standards, our unsatisfactory way of life, and our falling behind in the field of advanced technologies.”

But Gorbachev had to wait his turn. Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev died in 1982, and was succeeded by two other geriatric leaders: Yuri Andropov, Gorbachev’s mentor, and Konstantin Chernenko.

It wasn’t until March 1985, when Chernenko died, that the party finally chose a younger man to lead the country: Gorbachev. He was 54 years old.

His tenure was filled with rocky periods, including a poorly conceived anti-alcohol campaign, the Soviet military withdrawal from Afghanistan, and the Chernobyl nuclear disaster.

But starting in November 1985, Gorbachev began a series of attention-grabbing summit meetings with world leaders, especially U.S. Presidents Ronald Reagan and George Bush, which led to unprecedented, deep reductions in the American and Soviet nuclear arsenals.

After years of watching a parade of stodgy leaders in the Kremlin, Western leaders practically swooned over the charming, vigorous Gorbachev and his stylish, brainy wife.

But perceptions were very different at home. It was the first time since the death of Soviet founder Vladimir Lenin that the wife of a Soviet leader had played such a public role, and many Russians found Raisa Gorbachev showy and arrogant.

Although the rest of the world benefited from the changes Gorbachev wrought, the rickety Soviet economy collapsed in the process, bringing with it tremendous economic hardship for the country’s 290 million people.

In the final days of the Soviet Union, the economic decline accelerated into a steep skid. Hyper-inflation robbed most older people of their life’s savings. Factories shut down. Bread lines formed.

And popular hatred for Gorbachev and his wife, Raisa, grew. But the couple won sympathy in summer 1999 when it was revealed that Raisa Gorbachev was dying of leukemia.

During her final days, Gorbachev spoke daily with television reporters, and the lofty-sounding, wooden politician of old was suddenly seen as an emotional family man surrendering to deep grief.

Gorbachev worked on the Gorbachev Foundation, which he created to address global priorities in the post-Cold War period, and with the Green Cross foundation, which was formed in 1993 to help cultivate “a more harmonious relationship between humans and the environment.”

In 2000, Gorbachev took the helm of the small United Social Democratic Party in hopes it could fill the vacuum left by the Communist Party, which he said had failed to reform into a modern leftist party after the breakup of the Soviet Union. He resigned from the chairmanship in 2004.

He continued to comment on Russian politics as a senior statesman — even if many of his countrymen were no longer interested in what he had to say.

“The crisis in our country will continue for some time, possibly leading to even greater upheaval,” Gorbachev wrote in a memoir in 1996. “But Russia has irrevocably chosen the path of freedom, and no one can make it turn back to totalitarianism.”

Gorbachev veered between criticism and mild praise for Putin, who has been assailed for backtracking on the democratic achievements of the Gorbachev and Yeltsin eras.

While he said Putin did much to restore stability and prestige to Russia after the tumultuous decade following the Soviet collapse, Gorbachev protested growing limitations on media freedom, and in 2006 bought one of Russia’s last investigative newspapers, Novaya Gazeta.

Gorbachev also spoke out against Putin's invasion of Ukraine. A day after the Feb. 24 attack, he issued a statement calling for “an early cessation of hostilities and immediate start of peace negotiations."

“There is nothing more precious in the world than human lives. Negotiations and dialogue on the basis of mutual respect and recognition of interests are the only possible way to resolve the most acute contradictions and problems,” he said.

Gorbachev ventured into other new areas in his 70s, winning awards and kudos around the world. He won a Grammy in 2004 along with former U.S. President Bill Clinton and Italian actress Sophia Loren for their recording of Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf, and the United Nations named him a Champion of the Earth in 2006 for his environmental advocacy.

Gorbachev is survived by a daughter, Irina, and two granddaughters.

The official news agency Tass reported that he will be buried at Moscow’s Novodevichy cemetery next to his wife.

___

Vladimir Isachenkov and Kate de Pury in Moscow contributed.

Jim Heintz, The Associated Press