Regina – While there are commercial labs of all sorts, sometimes you need a specialty lab to really delve into a new area. That’s a primary role of the Saskatchewan Research Council (SRC). Among its facilities are their labs at 6 Research Drive, in the Innovation Place research park at the University of Regina.

Kelly Knorr is the operations manager of the energy division with SRC. On April 13 he took Pipeline Newsthrough a tour of the facilities.

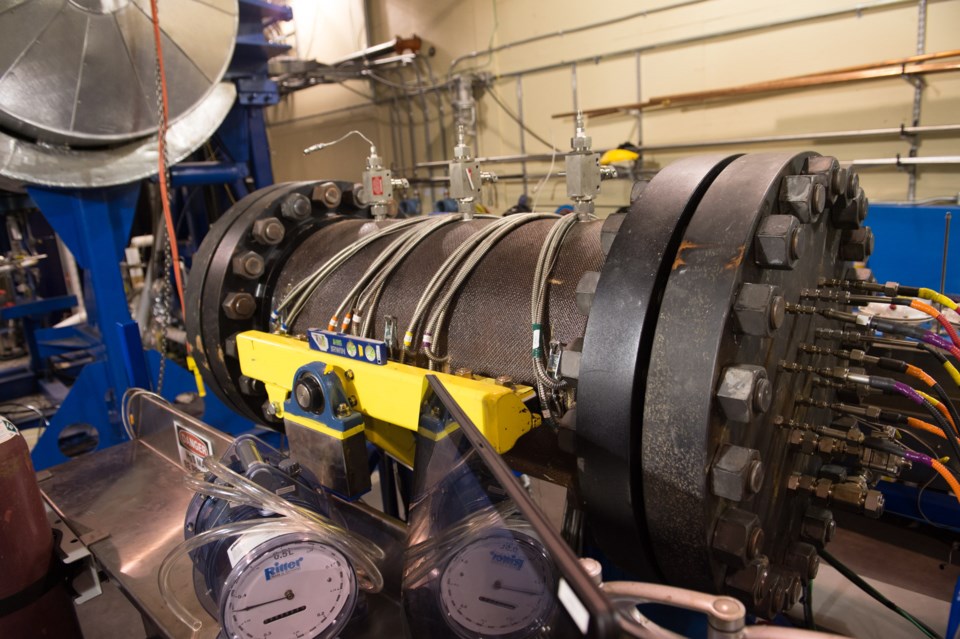

“In the Regina facility, we have three business units that operate. Two are enhanced oil recovery (EOR) units, and the third one is called process development. They deal mostly from the wellhead to the refinery,” Knorr said. “They deal with surface facilities, and a little bit of pipelining.”

Only three people work in the process development unit in Regina. The remainder work in Saskatoon, where SRC has another facility that does a lot of work with pipelines.

One of the EOR units looks at field development, the other looks at processes. ‚ÄúThey‚Äôre kind of separated by the type of oil –°¿∂ ”∆µ produced,‚Äù he said. ‚ÄúEOR process looks primarily at light and tight, through to the medium oil, and EOR field development looks at the medium oil through heavy oil, extra-heavy oil and oilsands.‚Äù

The laboratory for process engineering might look at samples off the wellhead, looking at densities, viscosities, gas:oil ratios, chromatographs, etc. “They also look at emulsions and how to treat emulsions,” he said.

At one point they built an emulsion treatment trailer that would go in the field to do testing. Demand for that sort of work shifted, however, and the trailer has recently been repurposed.

Knorr explained that industry shifted, and chemical companies started offering that sort of services, including it in their services to the operator, essentially free to the operator. SRC still does some third-party analysis. “We can go ahead, on behalf of the operator, because we’re a fee-for-services organization, we can test all these products like the service companies did themselves. We can validate or refute these results. We operate as that third party independent testing.”

The re-purposed trailer is not –°¿∂ ”∆µ used to test concepts for emulsion treatment that does not involve chemical additives, but rather chemical-physical processes. This would work by passing the emulsion through some sort of media. One such media tested includes the red rock used for landscaping front yards.

“This is a quasi-mechanical process, but it’s really a surface chemistry process,” he said.

This concept was initially studied in the 1980s, and is now –°¿∂ ”∆µ revisited.

“There is some benefit to pre-treating the oil, but in many cases you could add a marginal amount of additional chemical and get the same treatment. So we haven’t got a whole lot of traction with industry. But this is the kind of testing this initiative does,” Knorr said.

“Whenever you get into a downturn like this in industry, the first thing that goes away, really, is enhanced oil recovery, which has long windows of time – five to 10 years – before you get a lot of your money paid back. You start to focus on production optimization and cost reduction,” Knorr said.

When oil companies start talking optimization, the first stage is often things that can be done in the field, like modifying pumping. Near-wellbore cleanup techniques is next, clearing out wax or asphtaltenes, for instance. Next is near-wellbore stimulations, out more than a metre or two. When it comes to radial flow converging around the well, small changes in the flow properties of the porous media, or the fluid itself, make a big difference in the overall pressure drop it takes to pull that fluid.¬Ý

A solvent stimulation or hot oil stimulation are possibilities. But these things have been done and, in the case of hot oil, are standard practice.

“When we talk about optimization, we say, rather than look at a long-term EOR-type of project, which most companies don’t want to look at right now, maybe we can move further out into this reservoir around the wellbore. So we’re out maybe five or 10 metres now? So we’re looking at that.”

Numerical simulation, different chemistry, different injection and production scenarios are all possible research areas.

When it comes to tight formations, like the Bakken, he said, “Multi-stage, massive fracs is a wellbore stimulation technique. You’ve already got most of the stimulation you’re ever going to do in these wells. In those cases, there’s probably not a whole lot of production optimization we can help them with. Their biggest problem is they’ve got fractures that will transmit the fluid, but the fluid isn’t in the fractures, it’s in the matrix. It needs to come out of a matrix that’s only got 0.01 milliDarcy permeability.

“What they can do, though, is maybe pressure support, like inject water or gas.”

The SRC hasn’t done any research on re-fracs, or doing a second hydraulic fracturing operation on a well several years after the initial frac.

Most research, he noted, is incremental. The industry, and the service companies in particular, come up with sea-change systems like the packers that allowed for multi-stage fracs. “That was a technology sea-change that allowed us to produce the Bakken in southeast Saskatchewan,” Knorr said.

Production operations and optimizations are looked at in one of the labs. It’s populated with centrifuges and microscopes as just some of the tools used for analysis. Two microscopes are labelled “Fred” and “Barney.” There’s also a chromatograph.

“If we have a particularly difficult emulsion that’s hard to break … we’ll work on some chemicals. Usually it’s a combination of chemicals and heat in your treater that will break that emulsion,” he said.

On production optimization, Knorr said, ‚ÄúWe don‚Äôt have any magic bullets. We don‚Äôt have any magic processes (where) that we look at a field facility and say you‚Äôve got to do A. B and C and you‚Äôre going to get this much more oil. These things are areas we‚Äôre more interested in now, because of the downturn, because the operators are more interested. The fact remains: the best way to reduce costs is to increase production, because your per unit costs goes down. A lot of the oilfield is fixed costs, where you‚Äôre amortized against whatever oil production you have. If you increase production, you‚Äôll reduce the per-barrel cost.‚Äù ¬Ý

Knorr said, “We are essentially an EOR shop, and we have been for 30 years. Now we have to adjust our focus a little bit to meet the needs of industry. The industry needs now have shifted to production optimization and cost reduction. So we’re starting to look at that. You can apply a lot of the same engineering, physics, and subject matter expertise and skill sets of the researchers to apply to these problems, to a limited extent. So we have a number of different projects we’ve started with a number of operators looking at specific things they want us to evaluate for them.”

Thus, the two EOR groups are –°¿∂ ”∆µ pulled in the optimization area, because that‚Äôs where the demand is now.¬Ý