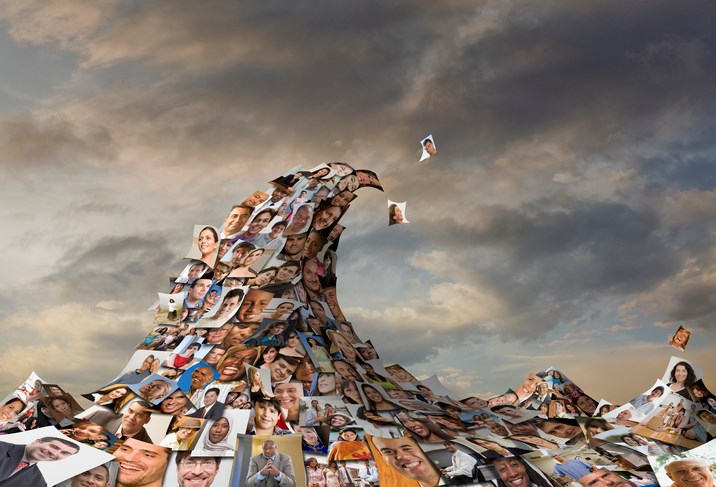

To mark 50 years of official multicultural policy this Friday, Metropolis Canada’s 4th Annual Forum on Measuring Identities kicked off on Oct. 6 with a poignant and provocative question: “Is multiculturalism just an ideal?”

The question, citing critics, was posed by Independent Ontario Senator Donna Dasko during her opening remarks at the virtual conference, which this year touched on themes of diversity, inclusion and eliminating racism.

Her comments, echoed by the other two panellists – Jean Augustine, former member of Parliament and minister of multiculturalism, and Calgary Mayor Naheed Nenshi – come at a time of increasing racist attacks and global anti-racism movements.

The conference – titled Multiculturalism @50: Diversity, Inclusion and Eliminating Racism – placed these issues within the context of Canada’s evolving multiculturalism, the recognition of which became official government policy on Oct. 8, 1971, making Canada the first country in the world to adopt such a policy.

“Multiculturalism reflects the cultural, racial (and) … religious diversity of Canadian society and acknowledges the freedom of all members … to preserve, to enhance and to share their cultural heritage,” said Augustine, who was called upon by the government to help develop Canada’s official multicultural policy 50 years ago.

But while Canadians “pride” themselves on diversity, she added, the inclusion of that diversity remains a question mark, to say the least.

“Do we truly look at the ways that our policies help with the diversity of all peoples? With these policies, were we really looking at all the effects of diversity on Canadians? Were we looking at all the ways that diversity needs inclusion to work effectively?”

Through both personal accounts and research findings, the panellists highlighted that the progress made over the last 50 years has come at the expense of immigrants and people of colour and much social and civil struggle.

‘Where are we in this picture?’

Canada’s multicultural policy has been described as an “accidental” response to the influx of immigrant settlers that took place as a result of the colonization of Indigenous lands.

Thus, while “Canada was always a diverse society, culturally speaking,” said Dasko – born and raised in Winnipeg (which she calls a “polyglot of a community”) – inclusion did not always follow.

Originally the home of the Métis Nation and located within Treaty No. 1, Winnipeg was settled by Francophone communities followed by an influx of British settlers from Ontario. From 1896 to 1914, another influx followed from Eastern and Central Europe, which included Dasko’s own Ukrainian grandparents. Germans, Russians, Jews, Mennonites and others followed.

As history has proven, this sea of European immigration did not lead to the “acceptance and respect of diversity” of those outside the “Anglo ideal,” she said, referring to non-white immigrants and Indigenous people, who were at a particular disadvantage.

“This diversity was not seen as desirable and was not embraced,” said Dasko. “The further your view or your group were from the Anglo ideal, the worse off you were and the lower you were on the social and economic hierarchy…It was a vertical mosaic.”

By the 1960s, as the baby boom generation was emerging and expectations of deference to authority and “existing hierarchies (were) in decline,” marginalized groups – from women to ethnic minorities to Indigenous Peoples to the LGBTQUI2+ community – began demanding “inclusion, equality and respect.”

However, the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Multiculturalism that came out of that moment during the government of Lester Pearson continued to fall short of inclusion, with its “sole focus on the so-called founding peoples – Anglophones and Francophones – proving to be problematic.”

“Spokespeople and leaders from other backgrounds and communities asked the legitimate question, ‘Where are we in this picture of the Two Peoples?'” said Dasko.

(Slow) Progress

The introduction of the new multiculturalism policy in 1971 was not universally accepted, namely by critics who worried about ethnic segregation and ghettoization, as well as Quebequers who have continuously argued that federal policy is not suited to its cultural reality. Indigenous peoples and nations are also “not adequately served by the multi-framework, given their aspirations and goals for self-government and treaty rights,” Dasko said.

Still, with the new policy came many social gains including the 1982 Charter of Rights and Freedoms which recognized the preservation of the multicultural character of Canada; and the Multicultural Act of 1988 which further entrenched the principles and practices of multiculturalism.

People’s attitudes have also evolved.

While through the ’70s and ’80s, a majority of Canadians complained about too much immigration, around the year 2000, attitudes “just switched,” said Dasko. “People didn’t think that anymore.”

According to her, a former public opinion researcher at Environics, in 1976, only 41 per cent of Canadians were aware of the multicultural policy compared to 79 per cent by 2002. In 1989, 63 per cent approved of multicultural policy, which went up to 74 per cent by 2002.

Regarding perceived effects of the policy, in 2002, Dasko found that three-quarters of Canadians felt the policy led to a greater understanding and equality of opportunity for all groups in Canada. Two-thirds of Canadians felt that greater national unity was also enhanced. Only one-third felt that national identity was eroded.

In 1985, 44 per cent of people felt that multiculturalism was very important to Canadian identity. By 2015, 88 per cent said it’s important overall to Canadian identity.

The percentage of people saying that immigration has a positive economic impact went from 56 per cent in the early ’90s to over 80 per cent in the early 2000s, “where that figure has remained over two decades.”

An ‘Unspoken Deal’

When Nenshi became Calgary’s mayor 11 years ago, he became Canada’s first and still only person of colour to be the mayor of a major Canadian city (also first Muslim mayor).

He considers this progress a “beacon of hope for Canada and for the world.”

Yet, he said, despite all the progress, “things feel differently now.”

Recalling his interaction with a group of Grade 12s in Calgary about how they had been instructed by their parents to respond when confronted by police, Nenshi mentioned how little the dial has moved on institutionalized racism when “kids (of colour) still get that lecture.”

“We live in different realities,” he said.

“People of colour have made a deal. It’s an unspoken deal…We’ll put up with it – with the security guard at the Walmart spending a little extra time with us; with ‘where are you really from?’; with questions about our capability when we get promoted – because, in return, we get to live here; in return, we get to live in a place of limitless potential for our kids.”

Like Jean Augustine said, “diversity is inviting everyone to the dance. But inclusion is making sure everyone is asked to dance.”