For my money, Paul Wells is one of the most astute observers on the Canadian political scene. He’s been around for a long time, has written for most prominent media outlets and published several books. If you fancy something fair but tough-minded on Stephen Harper, it would be hard to do better than (2013).

His latest prime ministerial offering is , subtitled Governing in Troubled Times. Published as part of the Sutherland Quarterly’s series of extended essays in soft-cover book form, it can be read in one or two sittings. I took two.

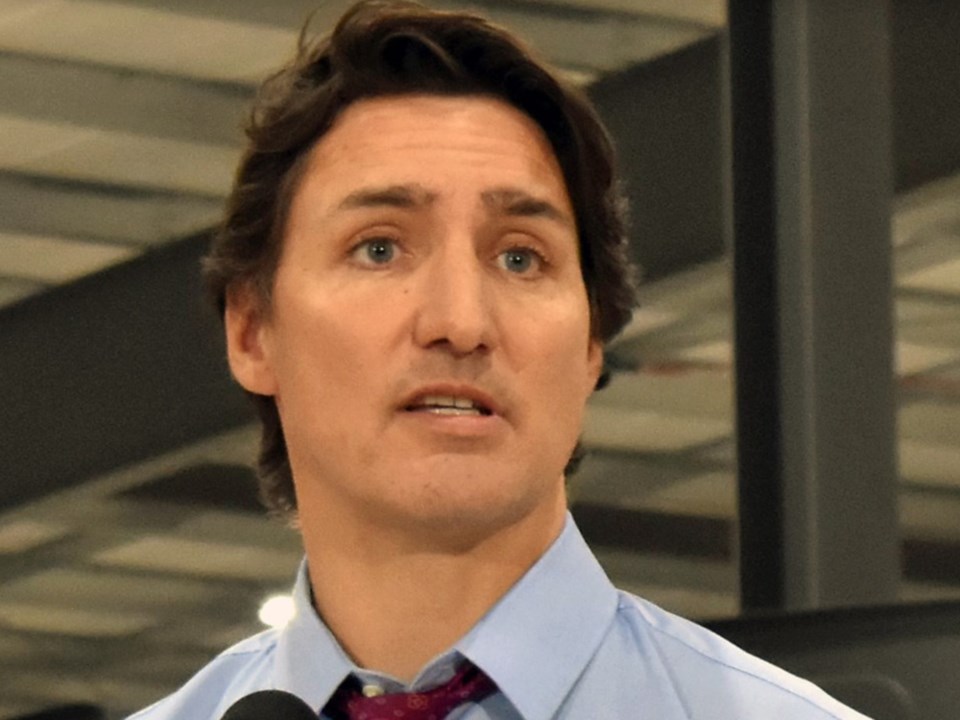

The Sutherland approach caps length at 100 pages and circa 25,000 words, thus rendering the subject matter accessible to people whose available time or interest might be incompatible with longer tomes. By way of context, the length of Justin Trudeau on the Ropes is about one-quarter that of the aforementioned Harper book.

And although Wells is critical of Trudeau, he’s by no means dismissive.

Yes, he notes the degree of birth entitlement. Born on Christmas Day as “the first child of a radiant Vancouver hippie newly married to a weirdly compelling prime minister whose political honeymoon was not yet over,” Trudeau’s initial claim of national attention was entirely unearned.

But, as Wells tells the story, there’s more to him than that.

In addition to –°¿∂ ”∆µ smarter than his detractors believe, Trudeau is emotionally perceptive, charming and adept at making a favourable first impression. He can also get some big things right, NAFTA –°¿∂ ”∆µ a prime case in point.

Immediately understanding the threat that Donald Trump’s NAFTA skepticism posed to Canada’s economic interests, Trudeau and his government organized “a massive, continent-wide program of constant contact between Canadian officials at multiple levels and absolutely anyone in the U.S. who could be made aware of the value of the bilateral trading relationship.” It worked.

Alas, though, the same level of managerial capability and focus hasn’t been evident on many other files.

Some readers, I suspect, will be struck by the chasm between Trudeau’s 2015 self-presentation and what transpired in subsequent years. If you anticipated a semi-reasonable alignment between promises and actual behaviour, disappointment beckoned.

For instance, unlike the reclusive Harper, Trudeau pledged to revive the practice of government by cabinet. Rather than ciphers destined to nod, smile and go along, Trudeau’s team would be strong individuals unafraid to speak their minds. And out of a clash of ideas and internal debate, wise policy would emerge.

But from the get-go, that’s not what happened.

Rather than –°¿∂ ”∆µ free to appoint their own chiefs of staff, cabinet ministers – including the likes of Finance Minister Bill Morneau and Justice Minister Jody Wilson-Raybould – had chiefs of staff imposed on them by Trudeau’s office. And there were also restrictions on cabinet ministers meeting without the presence of these minders. In Wells’ characterization, Trudeau’s governing style emerged as “an elaborate ritual of enforced conformity.”

Economically, the Trudeau of 2015 was positioned “perceptibly to Harper’s left, but not very far.” There’d be modest budget deficits, but only for two years. That promise, however, was “built on smoke” and jettisoned even before the pandemic-induced spending surge.

And perhaps the biggest disappointment came in terms of general tone.

Trudeau had castigated Harper’s government for its “inability to relate to or work with people who do not share its ideological predisposition.” In Harper’s world, disagreement and dissent were allegedly verboten. This was not how he, Trudeau, would do business!

The reality, again, turned out to be different; Trudeau became the master of the wedge issue, the man who would attempt to determine what was and was not acceptable to debate in Canada. Wells puts it this way: “Eventually, it wouldn’t be enough for Trudeau that his ministers think like him. Soon, he would expect the rest of us to do the same.”

Governing is, of course, very different from campaigning. In a December 1962 TV interview, John F. Kennedy was asked how –°¿∂ ”∆µ president compared with his expectations. His response showed a commendable capacity for self-awareness and learning: “Well, I think in the first place the problems are more difficult than I had imagined they were.”

No doubt, Justin Trudeau made a similar discovery and – however reluctantly – had to trim his sails as a consequence. If that’s the case, he won’t be the last prime minister to do so.

Then again, there’s an alternative explanation. Maybe the promise of “sunny ways” was always a con.

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps a little bit.

©