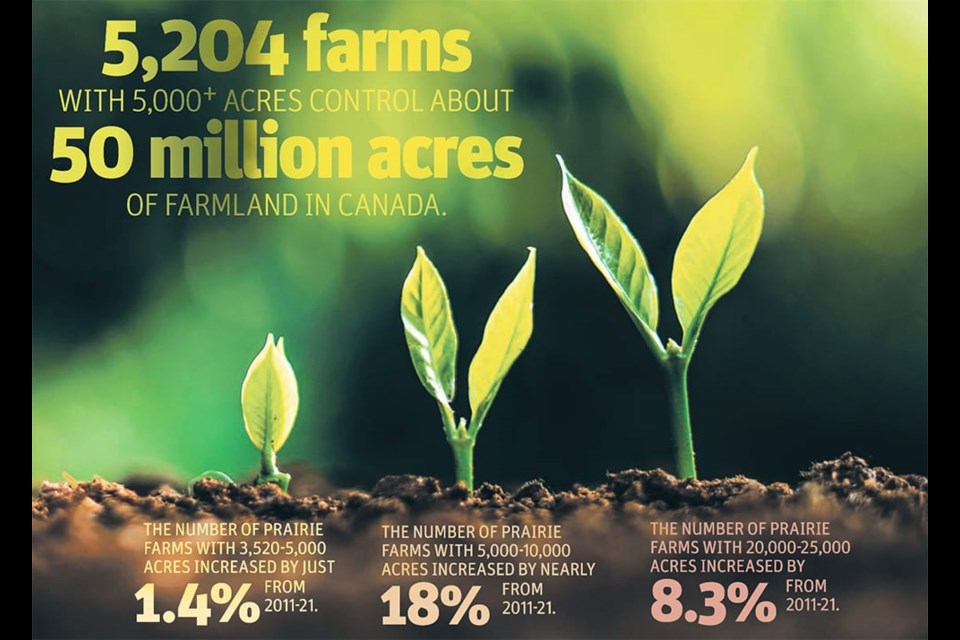

WESTERN PRODUCER — Assuming a large farm is 5,000 acres or more, 4,956 farms on the Prairies fell into that category in 2021.

Back in 2011, large farms owned and operated about 41 million acres of cropland and rangeland in the three prairie provinces. By 2021, they controlled about 46 million acres, having consolidated about five million acres in a single decade.

It was land once farmed by thousands of families. Some of them continue to own and rent out the land, but they are no longer growing grain or raising livestock.

The dominance is about more than acres. Big operators bring in the bulk of farm revenue.

“Farms in the top sales classes … account for the largest share of total farm operating revenues,” Statistics Canada said in May 2022. “In 2021, farms reporting at least $2 million in sales accounted for 51.5 percent of total farm operating revenues. This compared with 41.5 percent in 2016.”

The story of consolidation and concentration is not new. It’s been occurring for about 140 years, ever since immigrants from Europe arrived to claim the 160-acre plots in Western Canada that were offered by the federal government to encourage settlement.

Farms expanded by purchasing a neighbour’s farm or an uncle’s parcel, adding a quarter section here and a half section there.

What’s changed in the last 15 to 20 years is the money — and the size of the biggest farms.

“It (farming) is profitable. There’s big money in it,” said Evan Shout, chief financial officer of Hebert Grain Ventures, a 32,000 acre grain farm near Moosomin, Sask.

The “big money” part of farming is reflected in land prices. In 2001, a producer in eastern Saskatchewan needed $140,000 to buy 320 acres and expand his grain and cattle farm. Now, that same half section of land may cost $1 million or more.

The massive jump in land values since the early 2000s has essentially segregated farming into haves and have nots.

There are the haves, who bought land at the right time and now operate large farms in southeastern Saskatchewan. The have nots, who want to expand to 4,000 acres from 2,400, struggle to purchase land.

Over the last three to four years, dozens of farmers have told The Western Producer (usually off the record) that it’s become nearly impossible to buy land in their region of the Prairies. They relate various scenarios.

A neighbour’s land may sell privately before there’s a chance to make an offer. Or, owners of a 12,000 acre farm bid well above the asking price, pushing it beyond reach for a small acreage producer. Or, a farmland investment firm buys all available land.

Many of those thwarted buyers direct their anger at the 20,000 or 50,000-acre mega-farms in Western Canada. Others blame farmland investors.

In many cases, the grievances are shared privately over coffee but frustrations also seep into social media. The tweets and Facebook posts aren’t always made by farmers.

“One day corporations will own the entirety of this province’s (Saskatchewan) farmland,” tweeted Kyle Anderson, a molecular biologist. “We will return to the feudal Lords, Barons and Dukes profiting from doing nothing but owning the land, while Saskatchewan peasants toil at low wage & insecure jobs on their estates.”

Shout has read many comments like this about large farms and investor ownership.

“We all know that social media has made it easier for critics and it’s made it easier for the smaller minority to be very vocal.”

When he was in his teens and 20s, Shout might have agreed with some of the tweets. Maybe not the stuff about feudal lords and toiling peasants, but perhaps the notion that big farms are a negative.

“Growing up, my opinions were similar to most: large farms were hurting agriculture,” he wrote in a blog this spring. “Now, two decades later, I have drastically different views and a considerably larger amount of data on the subject. Not that I think consolidation is always a good thing, but I do believe that it is going to happen whether you like it or not. We can sit and complain or be part of the progress.”

Shout grew up on a grain farm near Watrous, Sask., and earned a Chartered Professional Accountant designation while working with his dad on the farm. He then took a job with MNP, where he got a first-hand look at the financials for dozens of farm businesses.

It shifted his thinking about large farms but his viewpoint really changed after he became the chief financial officer and part owner of Hebert Grain Ventures.

Shout learned that farms don’t get bigger just because they can. The main driver of expansion is right-sizing for the number of people involved.

“It’s not about the consolidation of acres. Even at HGV, we don’t have an acreage goal. It’s a people goal; having the right amount of acres (for) the team we want in place,” he said.

“Even as a 4,000 acre farm (where) you’ve got a father and son, you set up the acres for the number of people…. Our farm at HGV, which is 30,000, it’s about having enough acres for the people that we’ve hired.”

Hebert Grain Ventures calculates that one employee can manage about 2,000 acres of grain land.

“It’s an internal number,” Shout said.

The figure may explain why the number of farms in the 5,000-15,000 acre category is expanding in Western Canada. Such farms are large enough to support multiple families.

In 2011, Saskatchewan and Alberta had 3,322 farms in that category

By 2021, there were 3,941 for a gain of 19 percent.

Comments directed at large farms and mega farms usually begin and end with the same criticism — they kill small towns in Canada. Such remarks come from every direction, including academia.

“What we’re finding is that ownership is in fewer and fewer hands and that has a really tangible effect on local communities. It empties out the countryside,” André Magnan, an associate professor of sociology and social studies at the University of Regina told the CBC last fall.

Shout has heard those arguments but he disagrees with the analysis. Hebert Grain Ventures employs 15 people and many of them live in eastern Saskatchewan.

“On our farm we had 40 (or so) kids at our last summer barbecue,” he said. “Blaming the farms for communities going under is almost laughable for me. I’ve seen how many families from our farm team live in the surrounding communities.”

Shout said it doesn’t matter whether someone works on a farm or owns a farm.

“They still live in the community… and their kids go to school, their kids play sports there…. We need just as many people per acre as the five family farms around us.”

But not all workers on a 10,000-acre cattle ranch or 30,000-acre grain farm are permanent residents of small towns. Some are temporary workers who leave after the harvest. Large farms often hire Europeans or Australians as seasonal workers because it’s the only option, Shout said.

No one else is willing to do the work.

Hebert Grain Ventures hires young people from around the world, but also tries to help rural communities. Earlier this year it started the Deep Roots Foundation to support people and towns in eastern Saskatchewan.

“This is something that we have been wanting to do for a long time and is really important to our team. We all live and have kids in these communities and we want to see them thrive here, whether it’s a new rink, hospital equipment or a 4-H club. We love rural Saskatchewan and want people to stay here,” Kristjan Hebert said in January.

Of course, not every 30,000 acre farmer gives money to the regional hospital or volunteers at the local curling rink. But some do.

In a 2021 paper called Stratification of Canadian Agriculture, agricultural economist Al Mussell wrote that mid-sized farms are disappearing in Canada. Two distinct parts of agriculture are emerging instead.

There’s small number of exceptionally large farms, which produce most of the ag commodities, and a huge number of small-scale producers, where farming is not the primary source of income.

The trend is problematic because Canada needs farms of all sizes, but Mussell didn’t blame the big players.

“Large farms have not expanded as the middle size has declined out of some nefarious intent,” wrote Mussell, research lead with Agri-Food Economic Systems in Ontario.

“It’s the outcome of free enterprise and competition and the leveraging of economies of size that creates our highly efficient agricultural system.”

Shout acknowledged that big farms have a competitive advantage when buying land. They likely have more access to capital and have the size to take on debt.

If 900 acres of farmland goes up for sale, a 2,500 acre farm might struggle to make the mortgage payments on that land.

“They don’t have the ability to average those (borrowing) costs over multiple acres…. It hurts the profitability per acre, quite significantly,” said Shout, who is also president of Maverick Ag, an agricultural consulting firm in Saskatoon.

“Land is getting extremely expensive and where interest rates have moved, it’s not economical for some small farms to make that leap…. Just 小蓝视频 able to make the payments, it’s getting to the point where some small farms won’t have that ability.”

Outside investors aren’t the reason for high land prices. In many regions, local producers compete for available land and drive prices higher.

There’s also the question of what’s driving resentment toward big farms. It could be related to regret.

Some large farms on the Prairies expanded 10 to 15 years ago, when land prices were cheaper. Why resent someone for taking a risk and making a decision at the right time, asked Shout.

“Ten years ago, if you asked a guy, (he said) land was overpriced. But if you had a chance to go back, you’d buy as much as you could,” he said.

“Do you actually hate the big farms for who they are and what they’re doing? Or do you hate them because they did something that you should have done 10 years ago?”

There are cases in which a producer with 20,000 acres buys a tract of marginal land, then bulldozes the trees and converts it to cropland. There are also cases where large farms drain a wetland to maximize field efficiency.

It’s up to provincial regulators to approve or crack down on such practices, and farms of all sizes can be guilty of breaking the rules.

The more positive spin is that bigger farms have the money and people to adopt technologies that reduce inputs, cut greenhouse gas emissions and make a farm more sustainable. Variable rate application, slow-release fertilizer and sectional control are examples.

Research from Olds College shows that many farms don’t use the best available technology because of cost or lack of skilled labour.

“Small farms can’t afford to buy equipment and implement technologies that would help them be more sustainable. We do need programs and financial incentives to help these smaller farms rather than holding it against them,” Hebert wrote in a blog posted in April.

“Since the large farms are the ones implementing sustainable technologies, it would be nice if we appreciated that aspect rather than criticizing these farms for growing, expanding and thriving.”

In his paper, Mussell said the decline of mid-sized farms and dominance of large farms can affect agri-retailers and businesses that depend on local producers.

“Bunge (2017) notes that ‘[local] farm-supply retailers and grain companies are pressured, since larger farms use their size to wrangle better deals’,” Mussell wrote. “Some customers will prefer this structure as it could be seen as eliminating the middleman. However, to some extent it weakens the local economic development spinoff from primary agriculture, and the integration of agriculture with the community.”

There may be fewer farmers but acres have not changed, Shout said.

“It’s still based on acres. Two 2,000-acre farms versus one 4,000-acre farm, it’s still the same amount of equipment and it’s still the same amount of inputs.”

With combines priced at $800,000 or more and used seed drills at $250,000, farmers need to get the largest possible return on those investments.

That’s one reason Robert Andjelic is convinced that large farms will get larger.

“Yes, 10,000- to 20,000-acre farms will be the norm. Even currently, we have quite a few tenants that farm double those numbers,” Andjelic said in a 2022 email to The Western Producer.

“Why would you be farming only 5,000 acres and underutilize that equipment? Your costs for the equipment are the same whether you farm 5,000 or 10,000 with that equipment.”

Andjelic should know the numbers. He’s the founder and chief executive officer of Andjelic Land, which owns more than 230,000 acres of farmland in Saskatchewan.

He believes small scale farms will continue to exist on the Prairies, but they will fill more of a niche role in the ag sector.

“If the commodity (prices) are good, yes, they can survive with 3,000 to 5,000 acres,” he wrote. “The viability of the smaller farms depends on commodity prices.”

Economies of scale push farms to get larger but another factor could restrain consolidation: labour.

Canada doesn’t have enough people willing to work on farms and the shortage could get worse.

The Canadian Agricultural Human Resource Council has forecast that by 2029, grain and oilseed producers will need 10,000 workers to fill the shortfall.

Some farm businesses are already responding to the labour crisis.

“It’s got to the point where farms are actually turning down (land) opportunities because they know they can’t find the labour,” Shout said. “I’m predicting it’s going to have a larger effect on consolidation, going forward.”

Still, the trend toward big and bigger will likely persist. Some worry about a future where two or three massive farms, or investors, control most of the land in a municipality.

Shout is more concerned about the efficiency and competitiveness of Canada’s ag sector. His data shows a large gap between the top 20 percent of grain producers who are highly efficient and profitable versus those who only make money when prices are strong.

“I worry more about the industry…. Do we want agriculture to stay as it’s always been? Or do we want it to advance… and move forward?

“Can a 3,000-acre farm survive? They can if they have strong management and they adapt to change and they keep up with the industry and they’re progressive. But if they’re complacent and just want to stay (the same)? No. I don’t believe in 10 years from now that farm will still be there.”