DENVER (AP) ŌĆö About the only time ever disappointed his teammates was when he first arrived in Denver as the Broncos' first-round draft pick in 1974.

Eagerly awaiting the arrival of the man Ohio State coach Woody Hayes called ŌĆ£the best linebacker I ever coached,ŌĆØ were members of the budding ŌĆ£Orange CrushŌĆØ ensemble that would soon join Minnesota's ŌĆ£Purple People Eaters," Dallas' ŌĆ£Doomsday" and Pittsburgh's ŌĆ£Steel CurtainŌĆØ as one of the predominant defenses in the NFL.

Gradishar and nose tackle Rubin Carter, drafted a year later, would become the twin pillars of the ŌĆ£Orange CrushŌĆØ defense that served as the BroncosŌĆÖ backbone in the late 1970s and early 1980s and the driving force in their first Super Bowl appearance after the 1977 season, where they lost to Dallas 27-10.

Aside from what he'd bring to the field, his teammates wondered what kind of muscle car he might have spent his signing bonus on and if the rumbling V-8 engine or thumping subwoofers would announce his arrival from blocks away.

Gradishar instead rolled up in his father's creaky station wagon, the kind with the wooden side panels that were ferrying families across the country in the 1970s.

ŌĆ£We were like, ŌĆśWho is this guy?ŌĆÖŌĆØ recalled Tom Jackson with a hearty laugh.

Jackson ŌĆö who bought a gold Monte Carlo as a fourth-round pick one year earlier ŌĆö was a fellow Ohioan and former Louisville linebacker who would become Gradishar's roommate, lifelong friend and, come Saturday, his presenter.

ŌĆ£Then, of course, he started to play,ŌĆØ Jackson said, "and from that point on, we were like, ŌĆśOh, OK, weŌĆÖll follow this guy anywhere.ŌĆÖŌĆØ

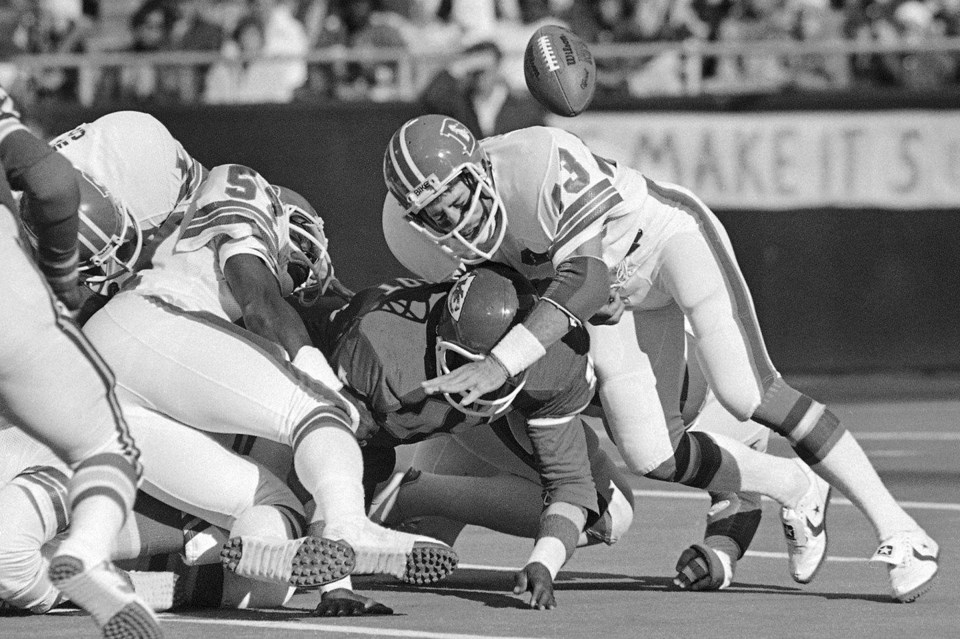

Gradishar wasn't a snarling linebacker in the mold of Jack Lambert, Dick Butkus or Lawrence Taylor. He was a tactician, deciphering offensive intentions with amazing accuracy and a superb athlete with an uncanny ability to stay on his feet and blow up plays.

A textbook tackler. Nothing fancy, nothing ferocious.

ŌĆ£Randy wasnŌĆÖt the fastest, he wasnŌĆÖt the quickest, he wasnŌĆÖt the strongest, heŌĆÖs just the most amazing tackling machine I had ever seen," Jackson said.

Joe Collier, Denver's longtime defensive coordinator and , told The Associated Press in an interview two weeks before his death in May at age 91 that the secret to Gradishar's greatness was his astonishing ability to stay on his feet when opponents tried to take out his legs.

ŌĆ£He had a sense of balance that always amazed me, how he would ward off blockers,ŌĆØ recounted Collier, who found in Gradishar the ideal captain for his 3-4 defense that was just gaining a foothold in the league in the mid-1970s.

ŌĆ£Guys would go after his legs and he would just skirt over these guys and stay on his feet. So, he was a guy that would be available for tackling 100% of the time," Collier said. "He was always around the ball. He wouldnŌĆÖt get knocked down. He wasnŌĆÖt a get-knocked-down type of guy.ŌĆØ

Like his choice of transportation, Gradishar's play was simply dependable and trustworthy, traits he learned growing up in Champion Township, Ohio ŌĆö a mere 40-minute drive from Canton ŌĆö where he began working at his father's grocery store at age 11.

That work ethic helped make him a high school star on the hardwood and the gridiron but he planned to focus on the family business after graduation until the school called him one afternoon while he was sweeping the store.

ŌĆ£They told me Woody Hayes was there to see me. I said, ŌĆÖOK, IŌĆÖll be right there,ŌĆØ Gradishar recounted. ŌĆ£Then, I hung up and I said, ŌĆśWhoŌĆÖs Woody Hayes?ŌĆśŌĆØ

Gardishar might have been the only kid in Ohio who didn't know that. But he hustled to Champion High School in Warren to meet Hayes before driving him back to the grocery store. When Jim Gradishar finished slicing bologna, he sat down with Hayes and the two of them talked for an hour, mostly about having both served in World War II.

After Hayes left, the elder Gradishar told his son he'd be attending Ohio State. So, off he went to Columbus to hone the skills that would make him an All-Pro in Denver, the AP Defensive Player of the Year in 1978 ŌĆö and after a 35-year wait, a Pro Football Hall of Famer at age 72.

ŌĆ£IŌĆÖm just glad it finally happened, whether it was me or someone else, because I think we all know that the ŌĆśOrange CrushŌĆÖ has not been recognized and so finally the ŌĆśOrange CrushŌĆÖ is ąĪ└Č╩ėŲĄ recognized,ŌĆØ Gradishar said.

Proud to be first, he prays he's not the last.

Although the ŌĆ£Orange CrushŌĆØ tormented offenses for several seasons, laying the foundation for the success the franchise would enjoy under John Elway, a return to the Super Bowl proved out of reach.

That was one reason often cited for the Hall of Fame snubs of the ŌĆ£Orange Crush.ŌĆØ Another was the widely held notion that the gaudy tackling statistics of that era ŌĆö such as GradisharŌĆÖs 2,049 career stops over 10 seasons ŌĆömust have been embellished by the Broncos.

ŌĆ£You know what? I donŌĆÖt blame them for not believing the numbers because RandyŌĆÖs statistics were, in fact, unbelievable,ŌĆØ Jackson said. ŌĆ£But they were real. I saw them."

___

AP NFL:

Arnie Stapleton, The Associated Press