“(The women) are seen as gang members but, as they go through this, you see the narrative begin to change as they … redefine who they are, resurge their identities in different ways,” said Robert Henry, who collaborated with the women on the book.

“Survivance” and not “survival” was chosen for the title because “survivance is a process that individuals go through that survival is a part of: survival, resistance and resurgence,” Henry explained. “They’re doing more than surviving.”

By sharing their stories, the women, who chose different names than their own to share their stories, want other women to see “that there’s a way out, that there’s others who have gone through similar things.”

And it’s about more than –°¿∂ ”∆µ part of a street gang, says Henry. He says “street lifestyle” is a more appropriate term.

“Street gangs are just part of this idea of street lifestyle. And when we look at it through a lens of survivance we understand that individuals engage in street gangs at a particular time, but they’re involved in street lifestyles for a lot longer.” Street lifestyles is just a connection to a specific street and local street codes in relation to underground economies, he explained.

Henry admits the story of the six women wasn’t the one he set out to tell. When he was working on his doctorate degree he undertook a project with STR8 UP, talking to men on the streets in Saskatoon. STR8 UP is a grassroots non-profit that works with people to help get them out of the street gang lifestyle. He was approached by a couple of women and asked why their stories weren’t –°¿∂ ”∆µ told.

It got him thinking. He went to a community organization, made his pitch, and nine women came forward. Six women followed through with the project. The other three weren’t ready to share their stories in the same way, said Henry.

It wasn’t difficult to get the six women on board, partially because they were familiar with Henry through his STR8 UP work and partially because they knew Henry’s process meant they had control of their stories.

“I think that’s something that research has really ignored. When we are involved in community-engaged research this is part of working with communities. It’s allowing them the ability to also dictate what is happening with the outcomes. It’s an Indigenous way of –°¿∂ ”∆µ. It’s not my story to say. It’s theirs,” Henry said.

He interviewed the women numerous times, some of the interviews spanning months. The narratives went back to the women for their approvals, sometimes taking three or four runs “before it got into the space where they were happy with what was –°¿∂ ”∆µ said or they agreed to what was –°¿∂ ”∆µ said and they were okay with it.”

The women also chose photographs to go along with their narratives and sometimes the photos brought up “different memories and different ways of understanding who they were,” which led to revising the narratives.

Henry calls the work he undertook with the women a partnership “built around respect, reciprocity, relevancy and responsibility.”

Henry describes himself in the book’s introduction as a “white-coded Métis hetero.” He says it’s important to position himself “so that people understand that I’m also here trying to understand my privileges and the relationship I have, not just to the information that’s going on, but also to the ways in which we have to make sure our relationships with who we work with and the participants are always there.”

The women’s lives are complex, he says, with healthy relationships that have pulled them through and negative relationships that have pulled them down. Some of those negative relationships include child welfare, education, incarceration and jobs. Family relationships, as well as relationships through street lifestyle, can be both positive and negative.

“We see the way in which those relationships have to change,” he said.

“People just don’t wake up one morning and say, ‘I’m joining a gang.’ When we start looking at the issues that many of the women face, we see similarities going across and the impacts that colonization and settler colonialism have had on their families and continue to have on them as Indigenous women in these spaces.”

In telling their stories, says Henry, the women are also hoping to appeal to social workers and others to get to know them and not simply see them as file numbers.

As for the general public, Henry says they need to take these narratives as “powerful reminders” of the truth-telling that is necessary before reconciliation can be reached.

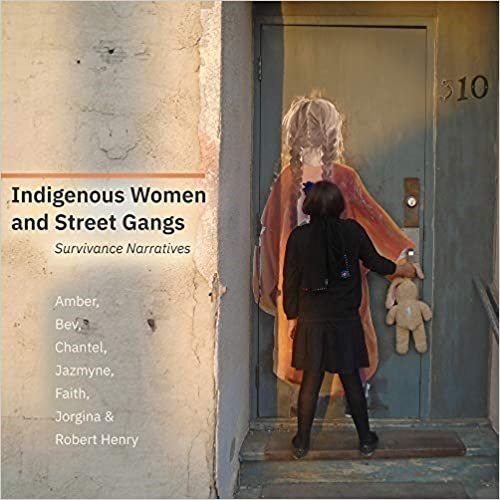

Indigenous Women and Street Gangs: Survivance Narratives is published by the University of Alberta Press.

It is available online or through Indigo/Chapters bookstores.