Despite Northwest Saskatchewan’s status among locals as a land of plenty — oil, wheat, livestock, fish, deer, berries — a place where lakes and cabins are only a short drive away, if you travel back in time to the late 1870s, after a particularly difficult winter, many of the Indigenous population were close to starvation.

After settlers arrived and the buffalo population had collapsed, Indian Agent James Stewart from Edmonton, (as noted in James Daschuk’s book, Clearing the Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvation, and the Loss of Indigenous Life) said that it seemed everything had deserted the country.

“…I have never seen anything like it since my long residence in this country. It was not only the want of buffalo, but everything else seems to have deserted the country,” he said in a report to the Canadian Government 144 years ago.

The Saskatchewan Telegraph — the first settler newspaper in the North West Territories at the time — painted a scene of deplorable conditions, one step removed from starvation, without rations, reaching a crisis point. Some had been left to eat only animal food. A distraught father, “skin and bones,” left for the plains after –°¿∂ ”∆µ unable to save his starving children.

He was reported to have succumbed to hunger himself.

“That in the event hereafter of the Indians comprised within this treaty –°¿∂ ”∆µ overtaken by any pestilence, or by a general famine, the Queen … will grant to the Indians assistance … sufficient to relieve the Indians from the calamity that shall have befallen them,” reads an excerpt from Treaty Six, promising relief in times of famine.

Fight against famine: The fall of a nation

Then, former Prime Minister John A. MacDonald stood in the House of Commons to say, Indigenous people should be kept as close as possible to starvation to ensure they continue to work.

“It is true that Indians so long as they are fed will not work. I have reason to believe that the [Indian] agents as a whole … are doing all they can, by refusing food until the Indians are on the verge of starvation to reduce the expense,” he said in the House of Commons in May of 1880.

Five years later, after Indigenous groups had fought back against the practices of the Canadian Government, the local Indigenous population was gathered on the grounds of Fort Battleford to see what happens when resistance fails.

“’We heard their necks snap,’” Maria Campbell, News-Optimist, April 18.

Just after 8 a.m. on Nov. 27, 1885, in the desolate North Saskatchewan plains near the Town of Battleford, eight Indigenous men stood with black hoods over their faces, nooses tight around their necks, and were killed in Canada’s largest and final mass execution.

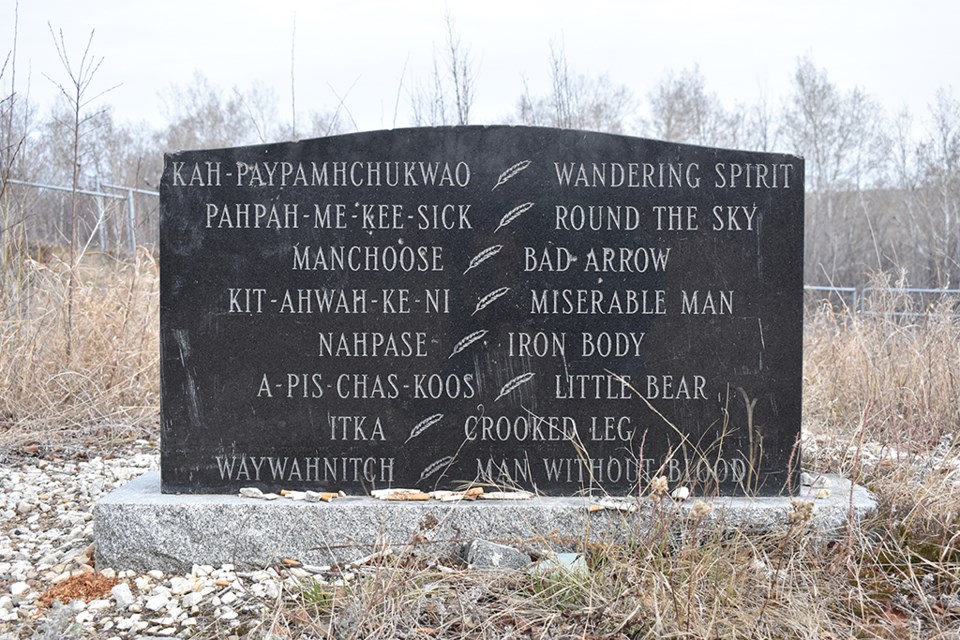

According to a 1972 edition of The Saskatchewan Indian and the stone grave marker on the bank of the North Saskatchewan River, their names were Kah–Paypamahchukways, Pah Pah-Me-Kee-Sick, Manchoose, Kit-Ahwah-Ke-Ni, Nahpase, A-Pis-Chas-Koos, Itka and Waywahnitch.

“’We heard their necks snap,’” Maria Campbell told an audience almost holding their breaths at the Saskatoon Public Library on a bitterly cold January evening as the city slipped into the early stages of slumber. She told the story of Mary PeeMee — the daughter-in-law of Big Bear — originally transcribed and published by Campbell in the 1970s, as frost clung to the windows outside.

“They were forced to watch the hangings so they would learn to be good Indians. ‘How could we forget?’ she said, speaking into silence so-thick, hurried breathing was audible in a room where extra guests gathered, standing, along the back wall.

“‘It was so quiet, even the wind was still.’”

Campbell originally told PeeMee’s stories in an issue of Maclean’s from the 1970s, stories that almost weep, palpable with grief, stuck between the periods and semicolons on the page.

In 2024, in Battleford, the men’s bodies lie in their unmarked graves while the North West Mounted Police graveyard stands prominently with waving flags and white gates on the hillside above.

But in Saskatoon, the Indigenous author, playwright and elder was resolute, her words lit alive at the podium. She told us that PeeMee though she was only eight years old when Wandering Spirit and the Indigenous warriors were hung in Battleford, standing in silence with the rest of the Indigenous children and adults brought from the local reserves to see the hangings.

She described the sexual abuse at Frog Lake, women and girls sold for rations. Michelle Good, in her visit to North Battleford in 2023, described people boiling and drinking tree bark to avoid starvation on the plains.

“’Those men [at Frog Lake] wouldn’t give rations to the starving people unless they serviced them first. And they had a place in the storeroom for that.

“’Often, they even demanded that the little girls be given to them, and they would play with them sexually in exchange for food.’”

Campbell notes that this didn’t happen to PeeMee because she was ugly.

“Many little girls were taught how to make themselves ugly,’” she added.

“As bad as it sounds, for me to say, what we need is truth,” Ray Fox, former North Battleford City Councillor, News-Optimist, March 21

It is horrors like this that have left a lasting impact on Indigenous people today in the Battlefords and area. This is evidenced by the hangings at Fort Battleford cropping up in contemporary Indigenous art — ranging from one of Louise Bernice Half-Sky Dancer’s grief-stricken poems read last year at the Saskatchewan Writers’ Guild 2023 Conference, or in Meryl McMaster’s portrait, I listened and the World Became Silent — and the legacy of trauma that Indigenous people say still linger.

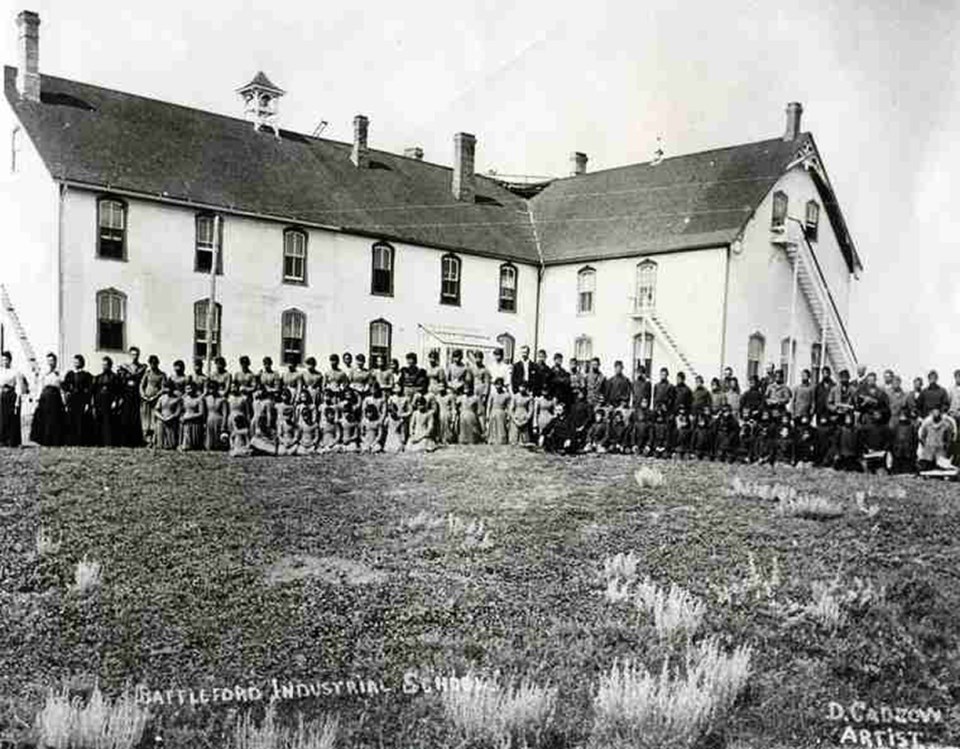

Hallowed legacy of Canada’s Residential School System

When Sweetgrass Woman — or using her colonial name, Isabelle Weenie — arrived at the St. Anthony’s Residential School near Onion Lake, Sask., she became known as number 46.

“When I went to residential school, we were not known by our names. We were all given numbers,” Weenie said, speaking at a public anti-racism community forum at the North Battleford Public Library on March 11, 2024.

For some reason, Weenie said, when Whelan Bonaise, a program coordinator for Battlefords Agency Tribal Chiefs (BATC) asked her to share her experiences at the event held jointly between BATC, the library, and the Multicultural Council of Saskatchewan, she agreed.

“On the drive here I asked the creator, or God … ‘help me so that I can make the people that are interested in our stories understand the history of Indian Residential Schools, what I went through,’” she said.

“I am a survivor. I was a victim. And I'm working on my healing journey. Just like a lot of other victims, survivors,” she said, noting that somehow, she still has her language despite –°¿∂ ”∆µ whipped in school if they used it.

Her parents never told the 68-year-old woman from Sweetgrass First Nation why they sent her to the school roughly 50 kilometres north of Lloydminster straddling the Saskatchewan and Alberta border. After fire destroyed the previous one in the 1920s, St. Anthony’s operated until 1974, and was a place where she spent seven years of her life and there subjected to near-constant verbal abuse.

Weenie gestured with her hands standing at the podium to show us how large the strap was that she was beaten with. She described the verbal abuse; how they used a certain string of words so often the children thought they must be good, kind words.

Weenie says the staff, in reality, were always saying, “Come here, savage.”

“I even hated God. I thought, ‘how could he do something like that to us,’” Isabelle Weenie, News-Optimist April 18.

“For myself, I resented what happened to me. I thought my parents didn’t love me,” she said, adding that she felt a sense of abandonment.

“What if you experienced that? Your children and grandchildren forced from your home? And you had no sense of power to say ‘no, I don't want them to go. Don't take them from me,’” she said.

When Weenie finally asked her mother 30 years later why she was sent, her mother said it was that or jail. They were forced to let her go. If they didn’t, Weenie says, they would have taken her away and she’d have never seen her parents again.

“I even hated God. I thought, ‘how could he do something like that to us.’”

She described the experience as if she was a zombie, only learning to say, ‘yes’ or ‘no,’ constantly terrified to get strapped or taken into a room with the priests or the brothers. Weenie said she used to have a reoccurring dream, running down a long hallway trying to escape the priests that chased her.

“It’s not something that we talk about. I’m able to talk about it because I’ve started my journey.

“It was difficult. And we had no power to say ‘No, don’t do that.’ Nobody was there to protect us. So, it continued,” she said, adding that today what people see in the Battlefords is because a lot of people don’t know how to deal with all this abuse and trauma.

The road to healing; overcoming grief

“It took me 20 years to finally see and understand what happened to me. I always thought it was my fault. I deserved it. It took me a while to see that it wasn't my fault,” she said, noting that it was her culture that saved her from becoming a statistic.

“I prayed so hard to him [the creator], I told him, ‘Help me, I want to be good, I want to feel good. I want my mama to say I love you,’” she said, as she fought a battle with alcoholism stemming from that trauma.

“We don't know how it feels. To hear somebody saying, ‘You're a good girl, you work hard. Never.”

Weenie’s husband passed away recently, and his final words to her were not to give up on life and not to give up on the youth or the parents in her community. Now Weenie works for her people. Recently, she said she worked for youth, taught them how to play sports, and even learned how to drive a bus which she did for three years. If she gets her way, next she’d like to drive a semi truck.

Weenie says that now she tries to spread some joy in her everyday life. Even if it’s non-verbal, she suggests everyone smile at someone they see in town. If you work with First Nations children smile at them, hug them, if they’re uncomfortable with that shake their hand.

“Because that is more meaningful. It brings peace to our hearts.

“Racism [comes] from these schools. And that’s the biggest problem in society. That there isn’t enough people like you and me, to help these people that can start their healing journeys.

“You may drive downtown, and you see them because nobody’s there for them … I don’t know what the answer is, but everybody –°¿∂ ”∆µ here is the start.

The long path forward: healing Indigenous trauma

Eleanore Sunchild, a well-known Indigenous lawyer from Thunderchild First Nation who still calls the Battlefords home, agrees. She says that hundreds of years of Indigenous trauma have successfully brought the population to their knees in what she calls “genocide.”

“For Indigenous people, I think reconciliation is healing. It's dealing with all the trauma that we've been subjected to as Indigenous people from residential schools, to foster care, to day schools,” she said in an interview with the News-Optimist.

“There's a lot of trauma in every Indigenous community, but you see it in North Battleford, because of the demographic and all of the reserves around North Battleford,” Sunchild added.

But while Indigenous people focus on healing, Sunchild says it’s up to settlers to acknowledge the colonial-based trauma that has been imposed on Indigenous people, and commit, if nothing else, to –°¿∂ ”∆µ compassionate.

“…[this area] really is the hotbed of racism in Canada, in so many different ways. And it’s psychologically entrenched, and it’s very historically rooted,” anti-racism facilitator, Becky Sasakamoose, News-Optimist, March 14.

“A lot of people think, ‘Oh, you know, Indians are just like that. They're just drunks, they just have a propensity to commit crime, like, why don't they get a job,’” Sunchild said.

“But if people knew about the true history and understood that there has been a cycle of colonization … it's ongoing, and it has never stopped … non-native people [have] to understand that this is ongoing. And then to be part of the solution.”

Sunchild — who owns Sunchild Law on Poundmaker land south of the Battlefords and who dealt with thousands of Residential School and Day School claims — says that the schools were full of physical and sexual violence and some of them didn’t close until the 90s.

“So, you're talking about generations of people who've been traumatized by Indian Residential Schools, by Indian Day Schools. And it just continues … people have just started talking about these issues.

“There's a real degree of healing that people need to do, but you can't always force healing … people have to have to want to heal.”

The intensely intergenerational power of trauma on reserve

Indigenous people need safe places to heal, Sunchild says. Safe places to tell their stories, to cry if that’s what’s needed to overcome that level of trauma that has been passed down intergenerationally, without the fear of people finding out in their small communities.

“And non-Indigenous people need to support that. So how do they support that? Well, it's just like helping lobby to get those trauma counselling centres that we need. It's understanding that we are seriously in a state of emergency from all of this trauma, it's leading to crime. It's leading to … addictions [to] these new drugs. And these new drugs are scary.

“Everybody’s trying to reconcile, but nobody's dealing with the truth,” former Battleford mayor, Chris Odishaw, News-Optimist March 21

“I truly believe that the high number of people who die within indigenous communities is directly correlated to trauma, said Sunchild.

“There has to be support, there has to be healing, lots and lots of healing, and lots and lots of compassion. And just –°¿∂ ”∆µ a human, you know? Just recognizing that Indigenous people are good people. We're beautiful people, we've been traumatized. And that's where you see the behaviour.

“We're really beautiful people, and so kind and so loving. And I think that non-Indigenous people can learn a lot about us, if they look through the narratives and the racism and the discrimination that they've been taught about indigenous people.”

The trauma is still readily apparent in Indigenous communities she noted, describing the work needed on reserves.

Christine Wahobin, the hereditary chief of Lean Man First Nation — who’s fight for recognition chronicled in a September 2019 edition of the News-Optimist still continues — said in an early January interview that something needs to be done on the reserve to address the violence that is happening there.

“You should go look at the reserve today … it’s not as it should be,” she said, despite a recent $141 million land settlement, Mosquito Grizzly Bears’ Head Lean Man First Nation had not been addressing her concerns.

“People don’t sleep, drugs are there, there are shootings now,” she said.

“And it’s not a good thing … all the time they just keep pushing money, money all the time.”

The resolution, she said is leadership on the reserve willing to stop the flow of drugs and violence present today.

“I’ve got a 26-year-old daughter … I questioned her, ‘what are you on, what are you using,’ and she says, ‘crack cocaine,’” Wahobin said, noting that her daughter was pregnant at the time.

“I just went right to the boys, the boys that are selling. There are two places I know of right now. That’s where I went.

“‘Don’t do that,’ I said. ‘Why do you want to do that to our people?’”

The News-Optimist’s requests for comment to chiefs at Mosquito Grizzly Bears’ Head Lean Man, Poundmaker, Red Pheasant, Sweetgrass, Moosomin, Saulteaux and Stoney Knoll First Nations near the Battleford were either declined or ignored.

Solution for bringing an end to trauma in and around the Battlefords

Moving forward while trying to heal, Sunchild says, includes supporting healing initiatives on reserve, lobbying the government for meaningful supports, getting services on reserve like drinking water and their own police forces, or even just –°¿∂ ”∆µ more compassionate to the trauma present. Another key, she notes, is education about the real history of the area to combat racism.

“But there's a lot of racism in North Battleford and Battleford. Like, it's, it's like living in the 1800s,” she said, noting that she’d had to leave North Battleford following the Gerald Stanley acquittal and the attack on an Indigenous man in North Battleford in 2022.

“I didn't feel safe there anymore as an Indigenous person. And I didn't feel that my children were safe.”

Even then, Sunchild says she doesn’t think there’s a solution where everyone’s going to come together and it’ll be a ‘happy, fairy world.’

“No, there has to be hard discussions about racism, discrimination. People have to look at what happened to Colton Boushie and have those conversations in our community because that cannot happen again.”

The key, she feels, overall, is education.

“You have to educate the next generation … frankly, some of the older generation knows they're never going to change and you're wasting your breath. But if you plant a seed in any young person's mind, and show them another way of thinking, then that's going to change the world.”

While Sunchild says she thinks change might be idealistic at this point. Either way it will take the community coming together and living in peace and friendship, sharing the land, sharing the resources like the treaties had wanted.

How long will it take?

“I don't know. It depends on the level of healing and education that people undertake, but it's going to take a while,” says Sunchild.

Indigenous justice lacking in North Battleford

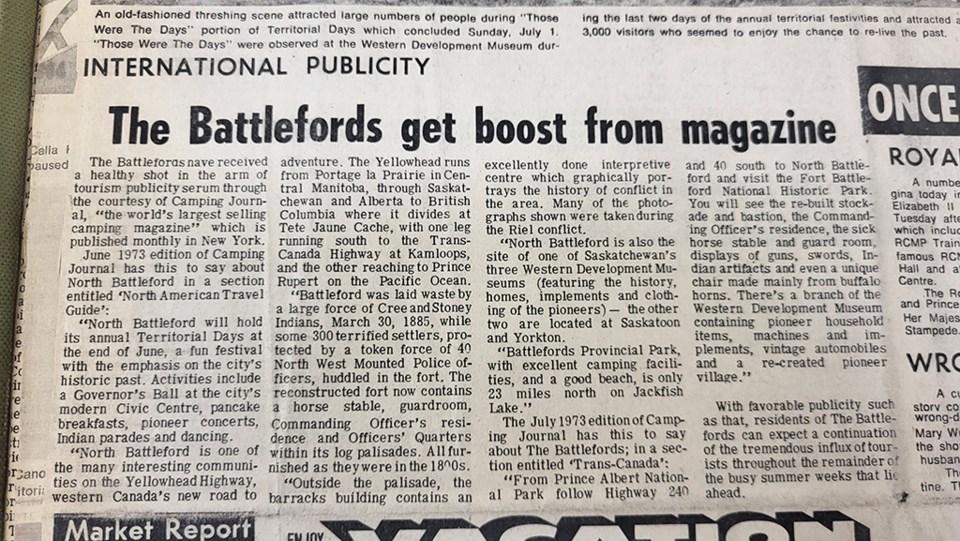

Jump back to1973 in North Battleford. While the incoming mayor of North Battleford spoke of infrastructure projects set to cost the city millions, an article from the same year informed readers that North Battleford had found itself with international coverage —of the good kind —and was –°¿∂ ”∆µ noticed as the centre of Saskatchewan's tourism.

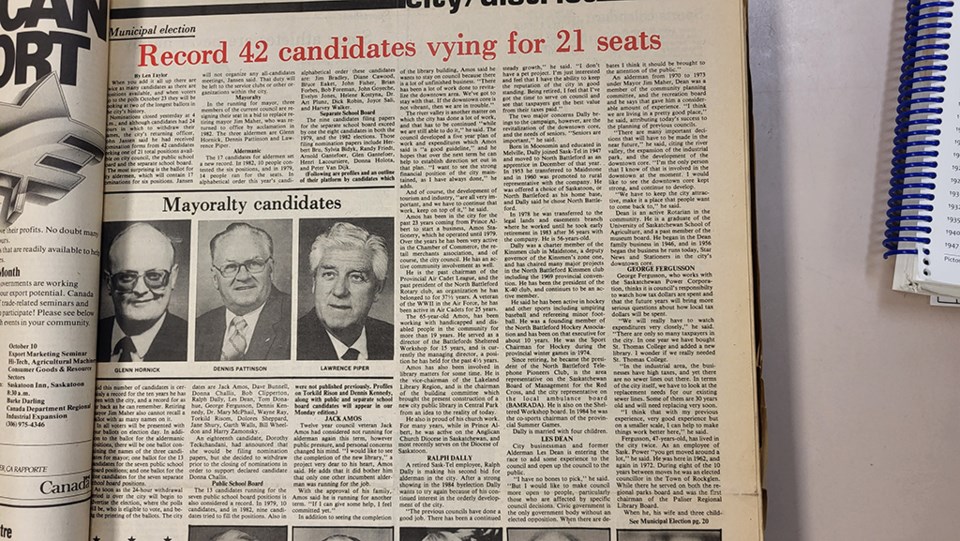

That year residents were writing letters to the editor applauding the beauty of the downtown's Christmas decorations, articles were penned mentioning a record-breaking turnout at the annual fair, and concerns over a lack of candidates running for council or vying to change things on council painted a picture of North Battleford before its current battle against crime and the stigma that followed.

So, what happened?

By the 1980s, cracks were showing in North Battleford. In the 1985 election, where a record-breaking 42 candidates were vying for 21 seats, there was mention of needing to revitalize the downtown. A federal report published in the 1980s in the News-Optimist described a death and unemployment rate several times higher than the national average for Indigenous people.

Then-reporter Linda Lewis wrote on July 11, 1980, that Brian Beresh, a director for the Legal Aid Clinic in North Battleford, anticipated expansion of the clinic, but not due to a rising crime rate. Going on to strike an expansive legal career across Canada, he maintains that crime in North Battleford cannot be understood solely by statistics.

When speaking with the News-Optimist, Beresh noted that before he left the Battlefords 43 years ago, a lot of the cases the clinic dealt with were property issues.

In a 2023 phone interview, he expanded on that, noting that property crimes directly correlate with some residents –°¿∂ ”∆µ stuck in different socioeconomic classes.

"We also track it back to an enhanced number of Indigenous citizens –°¿∂ ”∆µ charged, which leads back to a strong argument about the effect of racism within policing, and the criminal justice system, which is clearly reflected by the increased number of First Nations people in our prisons,” he told the News-Optimist.

"There was very little discussion of that issue outside of members of the legal profession, [43 years ago] who were involved with the criminal justice system. It was, my recollection, that there was a lot of denial," he said adding that "... North Battleford lived in this sort of paradoxical universe where it relied heavily for commerce on the reserves around North Battleford, but wanted to be seen as –°¿∂ ”∆µ harsh on crime."

When asked about whether he felt it was best practice to focus on the positive while trying to solve the systemic problems evidenced, he said "Absolutely not.”

Have we had historical issues that have caused us more angst? [Colten] Boushie or different situations? Absolutely … even go back in history? You know when there were the hangings in Battleford,” Chamber of Commerce COO, Linda Machniak, News-Optimist, April 4.

What improves society, is –°¿∂ ”∆µ able to deal with problems, not gloss over them or hide them, Beresh said.

“And North Battleford, in my view, has a lot of very positive elements. But it also has a dark history. And we can trace it back to the hanging of the … men on the banks of the North Saskatchewan River."

Over 30 years later, Maclean's Magazine published their now infamous 2017 article titled, Canada's most dangerous city, North Battleford, is fighting for its future, preceded by the CBC, then followed by the National Post, CTV and other national media.

Together, they began suggesting that North Battleford was not a safe place to live.

Is that true?

Is Canada’s ‘most dangerous city, fighting for its future, again?

When you enter North Battleford — perched along Highway 16, roughly four hours from Saskatchewan’s capital city of Regina — in the early hours of the morning on any Saturday during the summer months, the streets are quiet.

It’s a far cry from the stigma that haunts the Battlefords: of gang shootouts and homicides, excessive thefts, and random attacks that groups like the City of North Battleford and Chamber of Commerce, say are nearly mythological.

"Let's be honest we have a crime issue in the Battlefords," Town of Battleford mayor, Ames Leslie, News-Optimist, March 14

In March 2023, the mayor of Saskatchewan's seventh largest city stood at a podium in the basement of a local hotel. Among the topics of reconciliation, advanced education, and his council's support for local businesses, the ever-present topic of crime and public safety reared its head at the annual State of the City Address.

Mayor David Gillan told attendees at the hour-long event that several initiatives — including the creation of the RCMP's Gang Task Force and Crime Reduction Team, supporting the Citizens on Patrol Program, and working with the Town of Battleford and local Indigenous governments — are aiming to curb crime and reduce the CSI (Crime Severity Index) collected by Statistics Canada.

“This has been a priority for previous councils, and it continues to be a priority, of course, for this council, as we look at ways to reduce our ranking on this list ... you will actually see that our violent CSI index numbers are dropping," Gillan said.

By the end of July, only four months later, the City of North Battleford released a statement in anticipation of the 2022 CSI statistics –°¿∂ ”∆µ uploaded to the Government of Canada's website. Despite the mayor's previous comments and a decrease in CSI statistics, the city didn't seem as concerned with the statistics as it had been in March.

"With enforcement levels and resources at an all-time high in North Battleford, a rising CSI is to be expected. This means that the city’s RCMP detachment is doing its job."

City administration noted that several systemic issues are the true root of crime in the Battlefords and area, but they also criticized North Battleford's reputation as –°¿∂ ”∆µ Saskatchewan's, and by extension, Canada's, “Crimetown” was a shortsighted and inaccurate representation of the bigger picture issues faced by the community.

Recent initiatives to deter crime include a controversial bylaw that restricts the use of alleys between 11 p.m. and 6 a.m., their new protective services cost recovery bylaw to allows the city to charge property owners for recurring calls to a property, and a recent Community Safety and Well–°¿∂ ”∆µ plan set to bolster more support for housing, youth supports, transportation, and reconciliation.

“It [the CSI] is the dark cloud that hangs over the Battlefords,” Mayor David Gillan, News-Optimist, March 14

Now, in 2024, though the city and the RCMP say they don’t question the validity of the weighted Crime Severity Index published every year by Statistics Canada — used by some in the media to rank those highest and lowest on the list — there is a growing push across Western Canadian municipalities to push back on some concerns.

But some in the community feel that North Battleford isn’t addressing the issues head on, and that the CSI is going up, because the issues facing North Battleford have not gone away.

Chris Odishaw noted in a March 21 edition of the News-Optimist that issues like high taxation — which the city has recently pushed back on, in their State of the City address — a lack of housing, jobs, and crime play a large role in what’s wrong with the community.

“With a lot of these problems, we’re not going to be able to police our way out of it,” RCMP Inspector Jesse Gilbert, News-Optimist, March 28.

But as the RCMP Inspector Jesse Gilbert told the News-Optimist on March 23, if systemic issues aren’t resolved, nothing will get better.

Pulling at the root of issues in the Battlefords

Jose Pruden's mother, recently retired, has started volunteering at the soup kitchen in North Battleford. During the process, Pruden said that her mother had the chance to meet with a population she's unfamiliar with and learn about people and their stories, it has helped her understand what might be another way to solve crime in North Battleford beyond enforcement.

Pruden admits freely that there is good in North Battleford, but she worries if there isn't a united push to first solve systemic issues, the symptom — crime — risks not changing at all. Her job at Battle River Treaty 6 Health Centre (BRT6HC), firmly entrenched in downtown North Battleford, sees her and the organization offering services to people in what she calls ‘a community rooted in colonialism and racism.’

"We work in colonial racist systems ... when you have addictions, then you have people who get desperate and get involved in crime. So, everyone is really quick to blame addictions, but addiction is just another symptom like crime is ... it's not going to be fixed overnight," she said, describing poverty, difficulty accessing resources and a legacy of trauma leading to addictions.

“Our community in general needs to do some reconciliation,” Director for BRT6HC, Jose Pruden, News-Optimist, April 18.

Due to the nature of their organization, they spend a lot of time working on harm reduction in the form of needle exchange and giving out naloxone (medicine to reverse opioid overdose) to users. Coupled with other programs between the province's Health Authority and other organizations in the community, she says work is –°¿∂ ”∆µ done to provide support to those struggling with addictions.

"We don't want people to suffer," she said.

But does it go far enough? Pruden says beyond getting more funding from the provincial government to address these issues that plague the Battlefords, it's truly reconciliation and fighting to solve the deep-seated racism in North Battleford that will eventually end crime.

"I don't doubt, for many people in this community, it probably is dangerous. And I don't mean to the everyday person, I mean people who are on the streets or people who are involved in gang life because that's the only way they can stay alive. It probably is dangerous for them. But I think for most of us, we're not in danger.

"Our community in general needs to do some reconciliation ... reconciliation is a word that's used a lot, and I think it's more than just showing up at the museum and learning about the culture. It's about really learning from people's stories."

At the time of requesting an interview, Patty Whitecalf, BRT6HC's executive director, was concerned that their organization was asked to comment due to its status as an Indigenous organization. Whitecalf added that she was worried the News-Optimist might be pursuing a narrative that painted Indigenous people in a not-so-pleasant light.

When asked to discuss the concern in more detail, Pruden said that the fear stems from community members not understanding what drives crime, addiction, and mental health in the community.

“We recognize that cells aren't the best place for the majority of people who are suffering from those issues … where in the community can we get them some help?” Inspector Gilbert, News-Optimist, March 28

"You hear in this community that poverty drives crime, and a lot of Indigenous people are poor, so they must be driving crime ... we're really dealing with the mental health and addictions pieces of it," Pruden said.

Reconciliation key to saving the Battlefords?

Every year, at the end of September, the Battlefords turn orange as the community comes together to honour the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation. In 2022, on a dewy morning as the sun rose, locally elected officials, the RCMP, members of the media, elders, Indigenous leaders, and the public, gathered in a teepee to share in a pipe –°¿∂ ”∆µ and oral storytelling.

Later in the day, there were flag raisings at both town and city hall and speeches from dignitaries about the importance of coming together and moving forward. Pancake breakfasts, powwows and walks took place.

The RCMP told the News-Optimist that re-building relationships with Indigenous people is one of the RCMP’s more significant struggles.

"That's our responsibility to look after each other...we have to take those steps and not blame the system and not blame each other,” Tribal Chief with Battlefords Tribal Chiefs, Wayne Semaganis.

“There are definitely systemic and intergenerational issues that are coming to the forefront,” RCMP Inspector Jesse Gilbert said, noting that whether it’s addiction to drugs or alcohol or even a mental health issue, a lot of that can be traced back to trauma, or even intergenerational trauma.

“And a lot of the communities I've worked with, small Indigenous communities where … we know there's an issue, but there is nobody, there is no funding, there is no mental health worker, there's no addictions worker.”

The real resolution, in his perspective, is to treat these multi-faceted issues that face the Battlefords and outlying communities not individually, but as a region. To bring everyone together, whether it’s First Nations, settlers, local municipalities, or higher levels of government and other agencies.

It will take coming together to solve the issues facing the Battlefords.

“So, one of the things we tried to do more [was] we tried to have more involvement from the First Nations leadership and setting priorities. We tried to have our members attend more events, Indigenous recruiting has been a big push,” he said, adding that it’s across the division not just in North Battleford.

But even then, he noted the RCMP may not be the best at it.

“You can't take something that's happened over a hundred years and caused that much trauma, and then just all of a sudden deal with it,” he said, speaking to reconciliation within the RCMP.

“And we’re probably not great at it. I don’t think anybody’s got a handle on it, otherwise it would be fixed.”

But the end of the day every September 30, an orange teepee glows orange on King Hill — or the new teepee monument the city hopes will be built there to permanently overlook the community — and promises a better tomorrow. As the community fights to end racism, resolve Indigenous trauma, rekindle a connection between Indigenous and settler cultures, and learn to have compassion for each other, that promise of a better tomorrow might be the best we can hope for.

This is the final story in the Behind the Headlines series by Miguel Fenrich. Below find links to the previous stories.

Corrections have been made to this story to indicate the City of North Battleford has never claimed that the stigma that haunts the Battlefords or associated crime are nearly mythological, nor did they say at the 2023 State of the City that residents could expect to leave conversations about crime in the past. Further an error that suggested the city wasn’t concerned about the Crime Severity Index from the 2023 State of the City until later in the year should have read as follows, “Despite the mayor’s previous comments and a decrease in the CSI statistics, the city didn’t seem as concerned with the statistics as it had been in March.