GLASLYN, Sask. – It has been six decades since a brutal attack that killed a 20-year-old Indigenous man after a First Nations camp was raided by a group of nine white men. Disturbingly, justice was never served, as none of the accused were convicted of the crime.

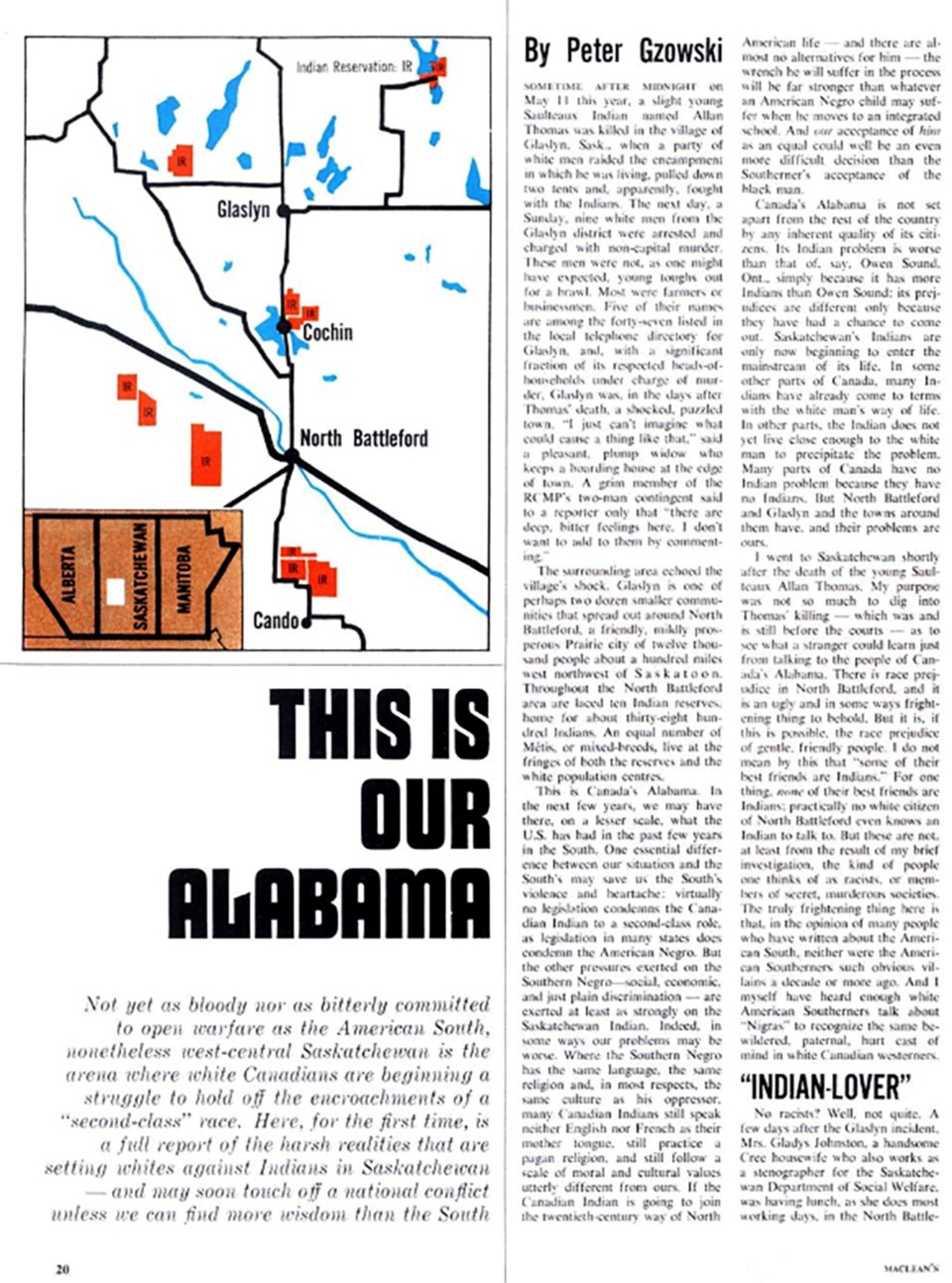

The devastating incident unfolded on the Glaslyn fairgrounds May 11, 1963, and forever etched a dark stain on Saskatchewan's history. The horrifying episode prompted renowned Canadian news magazine Maclean's to shed light on the heinous act of racial violence. In a poignant July 1963 article titled "This is our Alabama," penned by legendary journalist Peter Gzowski, the underlying racism in North Battleford – a small city about 67 kilometres south of Glaslyn – was unmasked.

“There is race prejudice in North Battleford, and it is an ugly and in some ways frightening thing to behold,” wrote Gzowski after spending time in the Battlefords when looking into Thomas’ murder. “But it is, if this is possible, the race prejudice of gentle, friendly people.

“Many parts of Canada have no Indian problem because they have no Indians,” wrote Gzowski. “But North Battleford and Glaslyn and the towns around them have and their problems are ours.”

Thomas’ vicious murder and Gzowski's haunting exposé shed light on the systemic racism and injustice that plagued Canadian society during that era. Reflecting on the 60-year anniversary of this tragic event, it serves as a reminder of the work yet to be done to address and eliminate racial prejudice in all its forms.

“The murder of Allan Thomas from the Saulteaux First Nation near North Battleford 60 years ago is a tragic reminder of the systemic racism our people have faced for many years,” Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations Vice Chief Edward Lerat, told SASKTODAY.ca in an interview.

“We have come a long way from 60 years ago. We currently recognize great work done by police leaders that have taken strides advancing First Nation issues in the Spirit of Reconciliation.

“Although we applaud good work, we continue to experience systemic racism at the hands of others,” added Lerat. “This comment is not only focused on police, when one looks at the incarceration ratio within the province or the victimization ratio, one realizes that we still have a long way to go to reach equity in justice for our people.”

A prominent Indigenous lawyer, and former Battleford resident, raised concerns over the lack of substantial progress in the battle against racism. Eleanore Sunchild asserts that racial prejudices persist.

“Not a lot [has changed], but people are more open with their racist views and there are more people denouncing and calling out racism,” Sunchild told SASKTODAY.ca in an interview.

“There is still much racism and it is dangerous because racism continues to kill and hurt Indigenous people,” said Sunchild, adding that more people, however, are calling out murder and violence for what it is."

North Battleford is a small city in west-central Saskatchewan. Just five kilometres away is the town of Battleford. Together, the communities are called the Battlefords and are the economic hub for the surrounding communities.

Despite hopes that the passage of decades would lead to significant changes, Sunchild affirms that the region still grapples with the same insidious forms of racism that have plagued it for generations.

In a candid statement, Sunchild said the fight against racism hasn’t made substantial headway. She said she continues to see "racist and dangerous actions" in the Battlefords and recently moved her family out of Battleford after her Indigenous friend was assaulted in her backyard in an unprovoked attack in July 2022.

The raid on the tents and murder

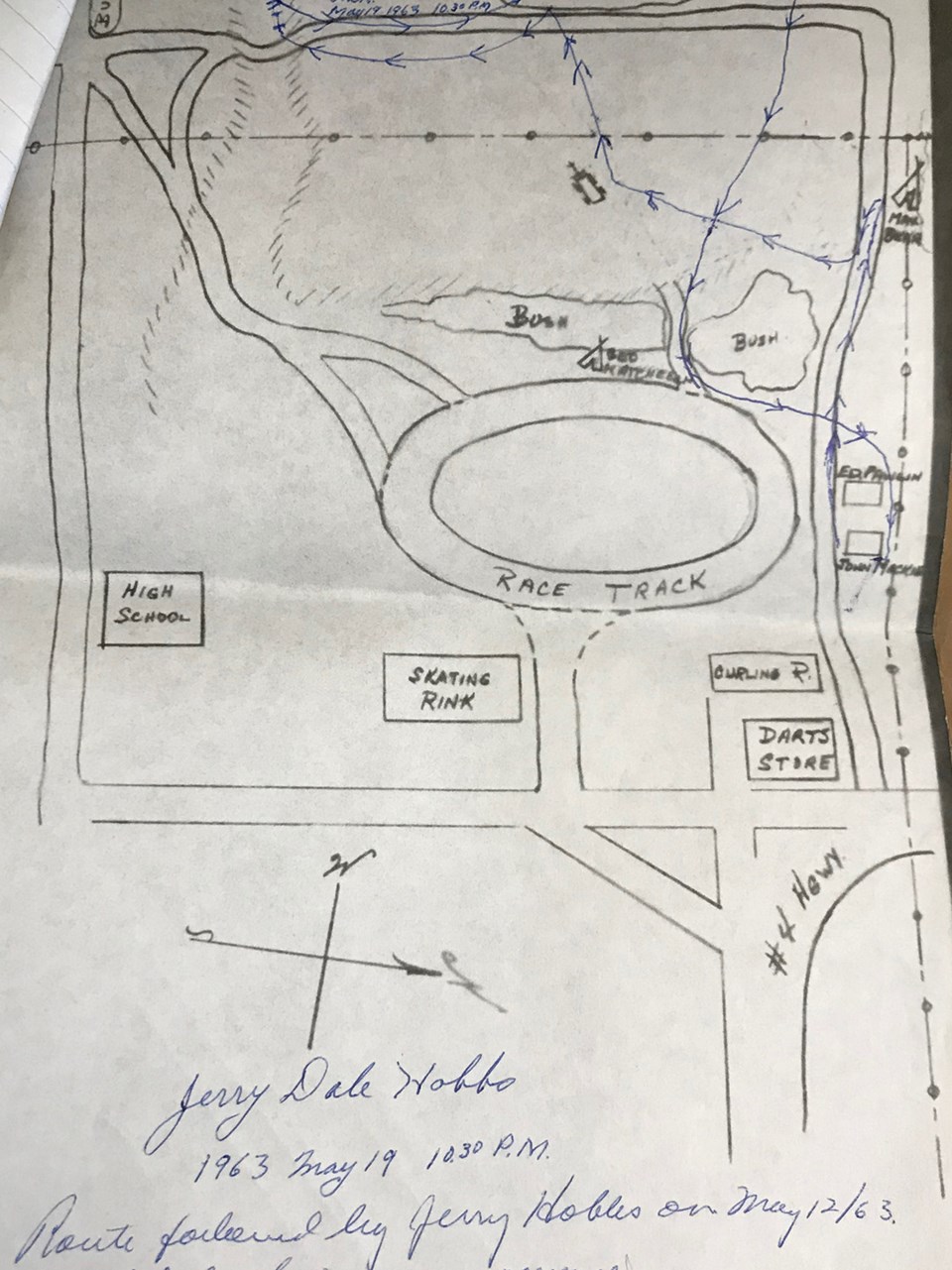

One of the nine accused individuals in Allan Thomas' murder, Jerry Dale Hobbs, said he came into Glaslyn around 10 p.m. Saturday night, May 11, 1963. The statement provided to RCMP, and obtained by SASKTODAY.ca from court records, sheds light on the murder case.

According to Hobbs’ police statement dated May 19, 1963, he said that he ended up at the local beer parlour, where he joined Alfred Lobe, George Batary, and a few others at their table.

“We had three glasses of beer and it was closing time,” said Hobbs. “We sat there and talked about farming and almost everything until about twenty minutes after eleven.”

The group of men took the party to Jack and Viola Mackie's home. Hobbs said that while standing outside of their house, “an Indian come up to us he says ‘what the hell you doing.’ Alfred said something to him, I don’t know what it was, and he walked up to Alfred right close and Alfred slapped him. He fell down on his backside.”

That was the extent of the encounter, according to Hobbs’ statement to RCMP. The Indigenous man left and the group of men went into Mackie’s house and drank more beer.

“We were sitting in the house for a while and then somebody said ‘are we going?’” Hobbs told RCMP. “I didn’t know what they meant. So everybody went outside. They said ‘we’re going to drive down to the Indian tents.’”

Nine men piled into two pick-up trucks driven by Alfred Lobe and Howard McConnell. They drove to the fairgrounds and then back to Mackie’s house.

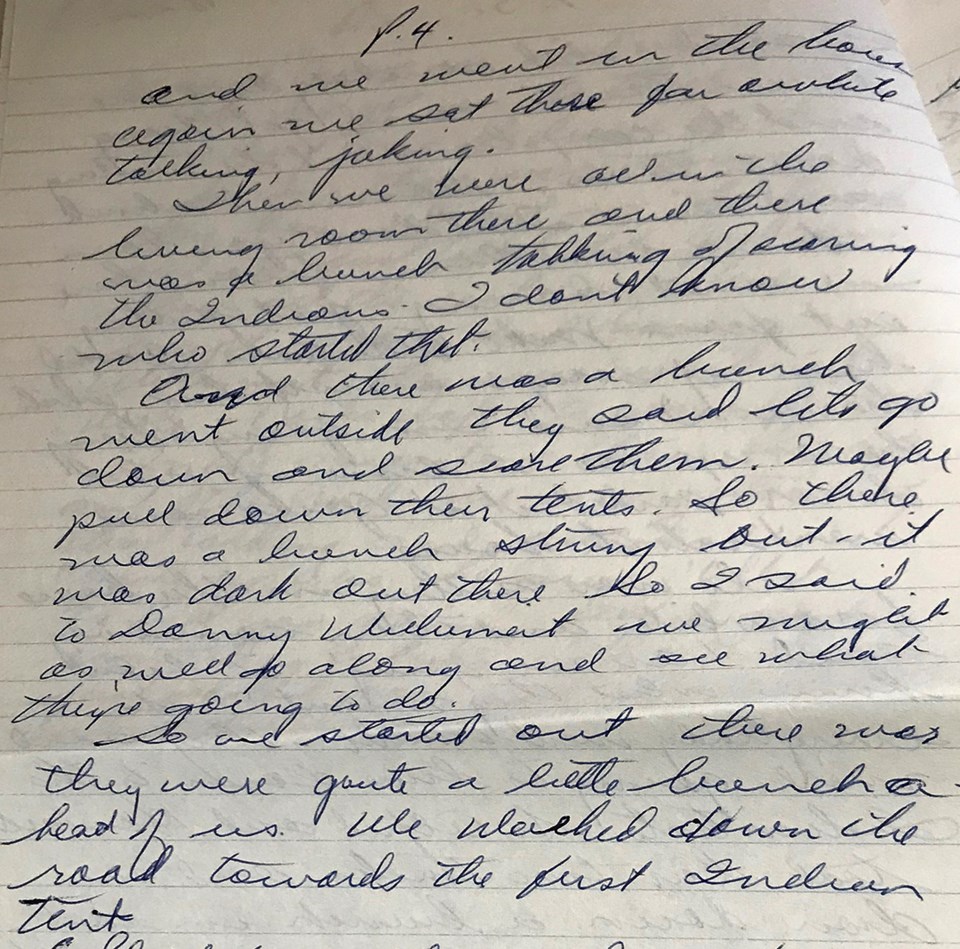

“We were all in the living room and there was a bunch talking of scaring the Indians,” Hobbs said in his statement to RCMP. “I don’t know who started that.

“A bunch went outside,” he added. “They said ‘let’s go down and scare them, maybe pull down their tents.’”

In May 1966, during the trial for Alfred Lobe, Howard McConnell, and Harold Michnik, Jack Mackie testified that he got into the cab of Lobe’s truck with another man whom he didn’t identify. The truck left Mackie’s and drove northwest. Lobe was driving. He turned in a field on the sports ground west of the village, made a circle and returned to Mackie’s. McConnell’s truck followed. The nine men went to the Glaslyn fairgrounds three times, court heard.

Hobbs, in his statement to RCMP, said they first approached Max Bear’s tent and then Bill Gopher’s tent. The tents were torn down and their contents strewn all over the ground.

During the trial for Lobe, McConnell, and Michnik, Crown witness Edward Thomas, a Saulteaux man from Cochin area, testified that he saw Alfred Lobe “running around” between two tents that had been knocked down, reported the Saskatoon Star-Phoenix.

Paul Moccasin, 20, of Cochin, testified at Alfred Lobe's preliminary hearing in January 1965 that he was with Allan Thomas at the camp west of the village “when some guys came there and were hitting us,” reported the North Battleford News-Optimist.

“I could recognize Alfred Lobe running around against the lights.” The lights he referred to were from the Village of Glaslyn.

During Alfred Lobe’s preliminary hearing in January 1965, Max Bear testified that while they were asleep “some guys tore the tent away and were kicking stuff,”

Bear said he didn’t see who they were because they were shining a flashlight. He told the court that when he asked the men why they were doing that they said, “You aren’t supposed to camp here,” reported the Saskatoon Star-Phoenix.

Cpl. H. Milburn testified during an inquest into Allan Thomas’ death that he had few complaints about the “Indian encampment” at the Glaslyn fairgrounds. He said the Indigenous people had been permitted to use the area for some years by consent of the Glaslyn village council.

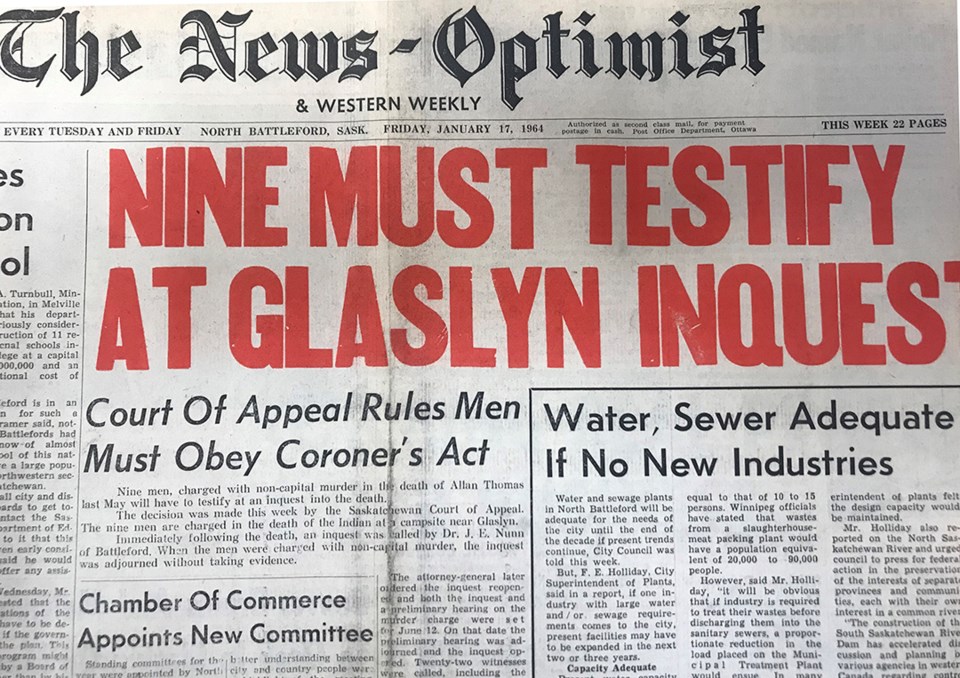

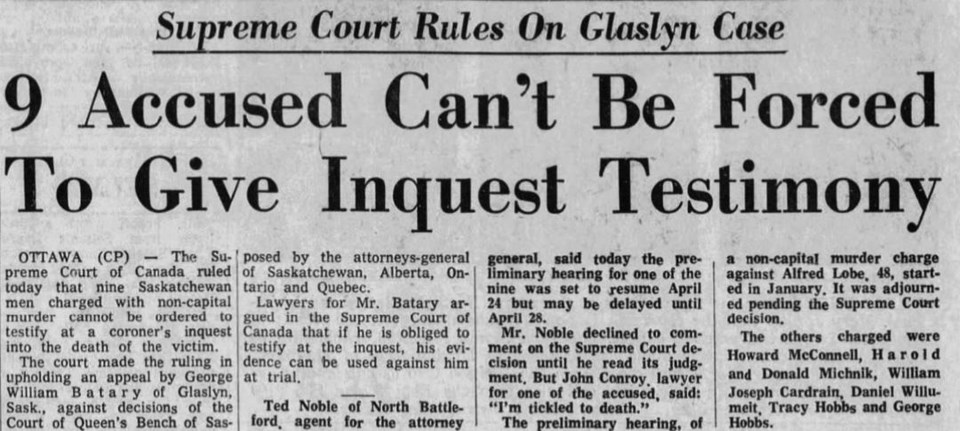

The inquest into Allan Thomas' death was adjourned after Batary's lawyer objected to him testifying. The Saskatchewan Court of Appeal had ruled that the nine accused must testify at the inquest into Allan Thomas' death. That ruling was taken to the Supreme Court of Canada, which struck down the lower court's ruling in April 1965. The inquest never reconvened.

At the May 1966 trial of Alfred Lobe, Howard McConnel, and Harold Michnik, Bill Gopher and his common-law wife Marlene Lewis, and William Clifford Martel testified in separate testimony that they had seen Alfred Lobe running around in the vicinity of the downed tents, reported the North Battleford News-Optimist.

Court also heard that Gopher had hit Lobe and Lobe was seen running away with “Gopher in pursuit” for about 50 yards. In the meantime, Michnik tried pulling Martel from behind the wheel of his car but ran away when he saw Gopher.

Max Bear told the court that he thought he recognized Donald Michnik’s voice. There were eight or nine men, he said, and one of them hit him in the eye.

Leona Katcheech, from Little Pine near Cutknife, testified that a group of men came to their tents that night and pulled them down. She said that there was a homemade stove in the tent and some items caught fire when the tent was knocked down.

At the time of the raid there was a 79-year-old grandmother and a three-year-old boy in the tents, court heard.

During the May 1966 trial, Paul Moccasin testified that he and several Indigenous people were drinking beer near the water tower in Glaslyn until about midnight on May 11, 1963, and were met at Bill Gopher’s tent by a number of “whites” who attacked them.

Thomas was running behind him he said when two white men caught them.

“They grabbed us by the hair and kicked us around,” testified Thomas, adding he didn’t know who they were.

Moccasin said he and Allan Thomas became separated as they fled. He testified that the next time he saw Thomas he was lying on the ground near Bill Gopher’s tent on his belly with one arm under him and one over his head and the RCMP were already at the campsite, reported the North Battleford News-Optimist. He said he helped Gopher load Thomas into Martel’s car.

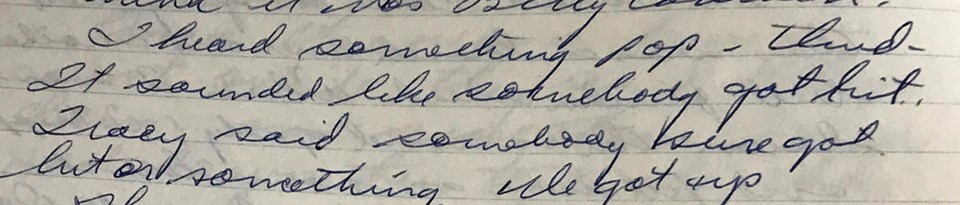

Hobbs, in his statement to RCMP, didn’t admit to participating in the tearing down of the tents and claimed he hid in a gully with Donny Willumeit, Billy Batary, Donald Tracy Hobbs, and Billy Cadrain. He said while they were in the gully, they heard a noise.

“I heard something pop – thud. It sounded like somebody got hit.”

RCMP officer Cpl. C. Evanoff arrived and patrolled the camp shortly after midnight, reported the North Battleford News-Optimist. The officer found Thomas lying injured on the ground near the tents of Bill and Alex Gopher. The officer told Clifford Martel and his wife Antoinette to take Thomas to a hospital at either Turtleford or North Battleford. They took him to the Indian Hospital in North Battleford where Dr. C. L. Chow pronounced him deceased shortly after arrival at 3:15 a.m., May 12, 1963.

Thomas’ skull was fractured and pathologist Dr. W. H. Houston testified in court that the injuries could have been caused by a car tire going over Thomas’ head. He also said the injuries could have been caused by a fall, reported the Edmonton Journal.

In his autopsy report Dr. Houston said death was due to cerebral compression from hemorrhages caused by laceration on the left side of the brain as a result of a fracture of the right side of the skull. The fracture was caused by a heavy blow to the head, reported the North Battleford News-Optimist.

During Alfred Lobe's preliminary hearing in January 1965, Cpl. Evanoff testified that on his way to the camp he saw vehicles and people standing outside the Mackie home. After going to the fairgrounds, he went back to the Mackie house and all of the accused were there except Harold Michnik who he said was asleep outside in a car, reported the North Battleford News-Optimist. At the time, the officer didn’t think Thomas was seriously injured but he warned the men that “it might be a more serious matter for them than knocking down a few tents.” He issued them a warning because they had been named as –°¿∂ ”∆µ in the camp area when the tents were torn down.

Cpl. Evanoff testified that Mackie objected to the “Indians pestering people in Glaslyn and to their camping so near to the village.” Objections were also voiced that the police weren’t doing enough about it, reported the North Battleford News-Optimist.

In court, Viola Mackie testified that the men were talking about going to the fairgrounds to “have some fun with the Indians.” She said that she warned Lobe to “leave them alone.” She said that after the raid she heard Alfred Lobe say, “I sure fixed that one,” reported the North Battleford News-Optimist.

George Batary testified that he was at Jack and Viola Mackie’s home on the evening in question. He said that on three occasions during the evening a group of men left the home. Afterwards, he testified that he heard Lobe say, “We fixed up one Indian.”

The arrests of nine white men

Starting the day after the attack, nine men were picked up by RCMP in a series of arrests and remanded in custody.

Lawrence Donald Michnik, 26; Harold Douglas Michnik, 22; Daniel Roy Willumeit, 31; George William Batary, 24; Jerry Dale Hobbs, 26; Alfred Irvin Lobe, 48; William Joseph Cadrain, 32; Donald Tracy Hobbs, 22; and Howard Joseph McConnell, 41, were charged with non-capital murder.

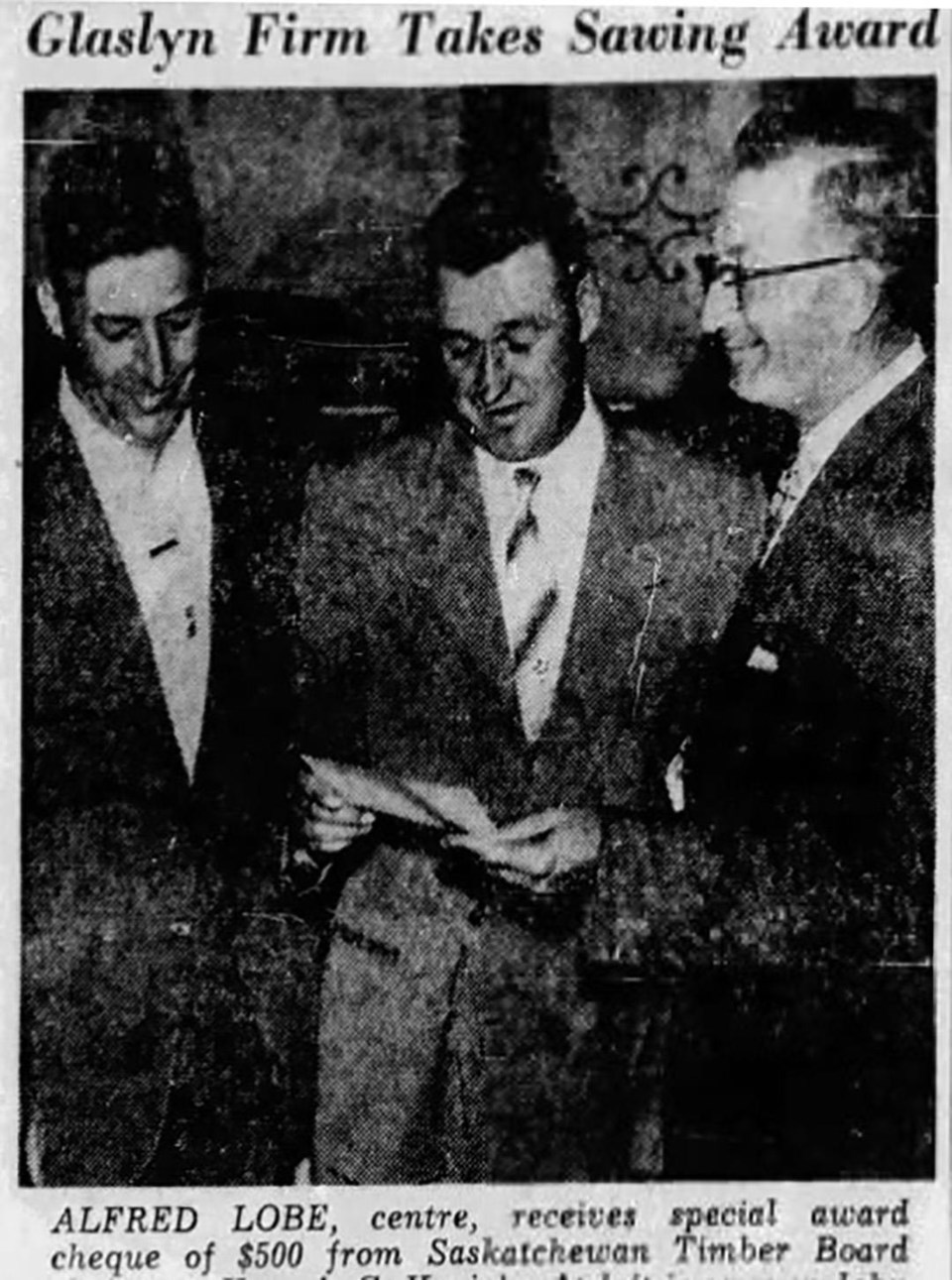

According to the North Battleford News-Optimist, Alfred Lobe and Howard McConnell were business partners in L & M Wood Products of Glaslyn. William Cadrain was an employee of L & M Wood Products. Harold Michnik, Lawrence Michnik, George Batary, Daniel Willumeit, Donald Hobbs, and Gerald Hobbs were farmers. Donald Hobbs and Gerald Hobbs were brothers. Harold Michnik and Lawrence Michnik were cousins.

All nine men were granted bail May 18, 1963, reported the North Battleford News-Optimist. Bail was set between $5,000 and $10,000 by Justice Donald C. Disbery in Saskatoon.

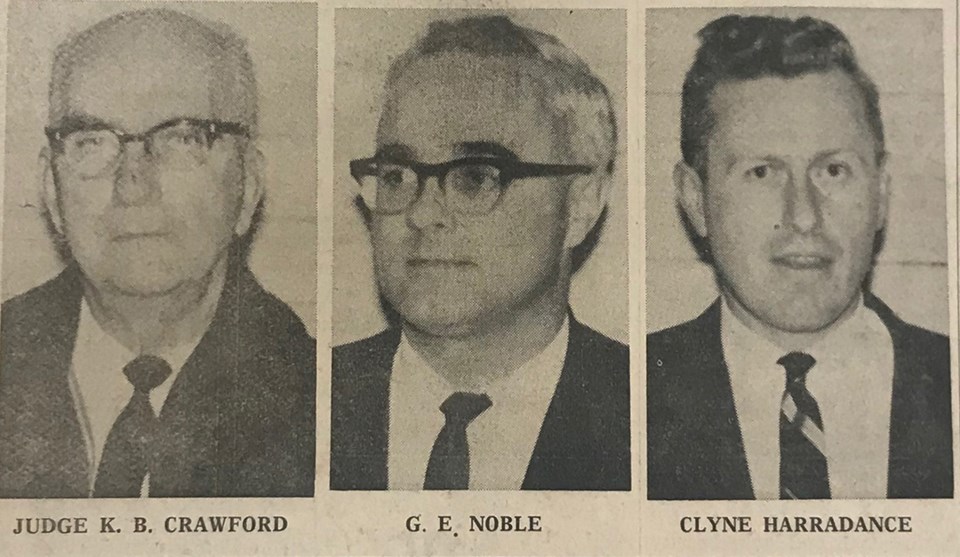

Clyne Harradance represented Alfred Lobe, John N. Conroy was Howard McConnell, Lawrence Michnik, George Batary and Gerald Hobbs’ lawyer. John H. Maher represented William Cadrain, Daniel Willumeit and Harold Michnik.

During the bail hearing, defence counsel John Maher told the judge that “all of the accused were respected men in their community,” reported the North Battleford News-Optimist.

Murder charges dismissed against all 9 accused: Manslaughter charges laid against 3

The non-capital murder charges were dismissed against the nine men because of a lack of evidence, reported the North Battleford News-Optimist. Three of the men, however, Alfred Lobe, Harold Michnik, and Howard McConnell, were then charged with manslaughter.

Following Alfred Lobe’s preliminary hearing held in the Legion in Glaslyn in January 1965, Judge K. B. Crawford of Meadow Lake said there was evidence that placed Alfred Lobe at the Bill Gopher tent where Allan Thomas had died, reported the North Battleford News-Optimist.

Tensions between Indigenous and town folk

Back then, many Indigenous families left their winter homes on the reserve in the spring and lived a nomadic lifestyle in tents. Glaslyn, with a population of about 150, served as a regular stop for these families.

The RCMP in North Battleford said the raid followed “some bad feelings between the town people and the Indians,” reported the Regina Leader-Post. The village’s mayor said he believed the raid resulted from a disagreement between one of the Indigenous men and several Glaslyn men.

An RCMP inspector told the Saskatoon Star-Phoenix that the Indigenous people had camped in the village and traded there for many years without difficulties. He said this was an isolated incident.

During Alfred Lobe’s preliminary hearing, a white woman described the Indigenous people as “pests” always asking for money and automobile rides.

Glaslyn residents had also complained that the Indigenous would drink in the village. Federal and provincial laws prevented Indigenous from buying or consuming alcohol on reservations, reported the Regina Leader-Post.

Casting suspicion on an Indigenous man

An RCMP officer testified during the trial that there was a possibility Allan Thomas may have been involved in a fight with another Indigenous man that night. He testified that Albert Moccasin disappeared immediately after Thomas’ body was found, had left some of his personal belongings behind, and hadn’t been seen in the three years since the murder.

Bill Gopher, however, testified that Moccasin was missing because he was in the penitentiary in Prince Albert.

Marvena Lewis testified that Moccasin was her brother and he was now back on the Moosomin Reserve near Cochin, reported the North Battleford News-Optimist. She told the court that at the time of the raid he was hit over the head with a three-foot long club and that he had left with the group of Indigenous people after the incident.

The manslaughter trial of Lobe, Michnik, and McConnell

During the trial in May 1966, prosecutor George E. Noble told the court in his opening statements, that the Crown would prove the three accused were guilty of killing Allan Thomas. He said that four Indigenous families had camped in tents adjacent to the fairgrounds in Glasyn: The Katcheech and Max Bear families from Little Pine First Nation, and two Gopher families, Bill and Alex from the Cochin area.

It was a dark night and identification was difficult, said Noble, but he added that Alfred Lobe, Harold Michnik and Howard McConnell were recognized. After the altercation, Allan Thomas was found lying on the ground, said Noble, as reported by the North Battleford News-Optimist.

Noble said the Indigenous people had been camping in that general location for a number of years. He said a group of "whites" gathered at the John Mackie residence, which was located somewhere near the tents. He said Lobe and eight others were present and there were indications that some drinking had been going on. Sometime during the evening, the topic of going to the fairgrounds and “molesting the Indians came up,” reported the North Battleford News-Optimist.

Jerry Hobbs was declared a hostile witness. He testified that he saw two figures in the darkness. He had made a statement to RCMP saying that Allan Thomas was on McConnell’s back and that he saw McConnell throw him to the ground. Hobbs changed his statement, however, when testifying and said he couldn’t be sure whether the men were McConnell and Thomas, or whether they were white or Indigenous.

Nellie Wilumeit was declared a hostile witness after repeatedly saying she couldn’t remember anything.

Alfred Lobe’s nephew Wayne Dyck, in a witness statement to RCMP on May 13, 1963, said some of the men jumped in the back of trucks and they drove around the field. The group later walked over to the fairgrounds, court heard.

“I guess the general idea was to see how many tents were pitched on the grounds in the field,” Dyck said in his statement to RCMP, which was obtained by SASKTODAY.ca.

“I overheard conversation amongst the remaining men in regards to raising a little hell with the Indians. It’s hard to see who talked. I believe they all talked about it. After a while, Harold Michnik, Alfred Lobe, Howard McConnell, Tracy Hobbs, Jerry Hobbs, Daniel Willumeit, Billy [William] Cadrain, [George] Billy Batary, Jack Mackie and I left the house.

"We sat and talked and drank some beer. Some of the men just at the house had been in the beer parlour, they had been drinking and appeared to be tipsy to me.”

Not guilty of manslaughter

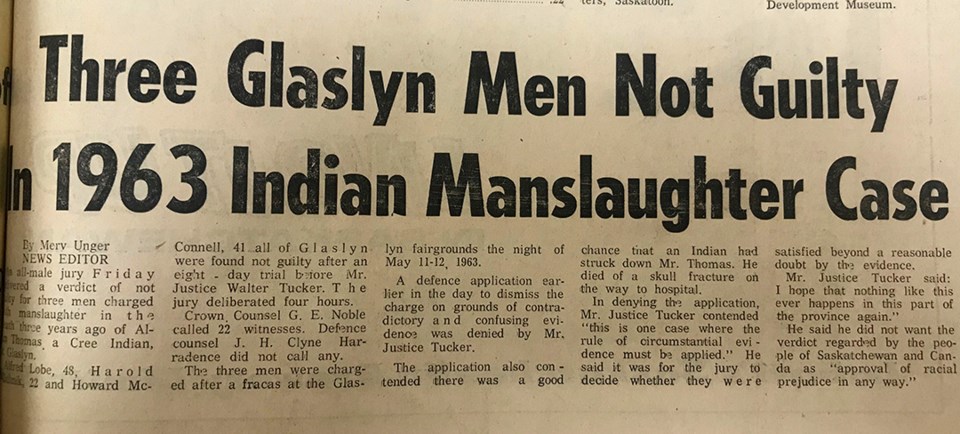

On May 13, 1966, following an eight-day trial at the Battleford Court of Queen's Bench, an all-male jury found Alfred Lobe, Howard McConnell, and Harold Michnik not guilty of manslaughter. The verdict was delivered after only four hours of deliberation.

Justice Walter Tucker, who presided over the trial, said, “This is one place where the rule of circumstantial evidence must be applied. There is evidence for the jury to consider. It is for them to say whether they are satisfied beyond any reasonable doubt as to the guilt or innocence of the accused," reported the North Battleford News-Optimist.

"I hope that nothing like this ever happens in this part of the province again," said Justice Tucker, as reported by the Edmonton Journal.

Justice Tucker also emphasized that he didn’t want the verdict to be regarded by the people of Saskatchewan and Canada as approval of racial prejudice in any way.

The aftermath

Justice has never been served for Allan Thomas or his family as none of the accused were convicted of the crime and as far as RCMP are concerned, the case is closed.

“The Saskatchewan RCMP Historical Crimes Unit has conducted a review of its historical files and can confirm there is no open investigation into the 1963 homicide of Allan Thomas,” Saskatchewan RCMP Media relations told SASKTODAY.ca in an email on May 10.

Alfred Lobe and Howard McConnell were partners in L & M Wood Products in Glaslyn. The operation had moved from the Prince Albert area to Glaslyn in 1962. L & M Wood Products changed its name to North Wind Forest Products. According to NWFP website, the company was sold in October 2018 to the Meadow Lake Tribal Council.

Alfred Lobe died Dec. 9, 2008, in Lloydminster, Alta., at the age of 92 and was buried in the Glaslyn cemetery.

An obituary for the wife of one of the other nine accused stated that she always said, “just because you got away with it doesn’t mean you won’t answer for it [whatever it was].”

Indigenous lawyer Eleanore Sunchild has a unique perspective on this decades-old murder.

“When I was a young girl and in the 60s scoop, my adoptive mother used to go visit one of those men accused in the murder of Allan Thomas,” Sunchild told SASKTODAY.ca. “I didn't realize that until I was much older when I started learning about the murder of Allan Thomas.

“The accused was very nervous and he was anxiety-ridden,” she added. “He drank a lot and I used to wonder what was wrong with him. I reflect on the impact of what he did and how he had to live with it. I think that it really impacted him for the rest of his life. So even though these men were not held accountable for the murder in the justice system they ultimately paid for their act, in some way."

Sunchild said that racial violence against Indigenous people is rooted in white supremacy and a false sense of that superiority based in fear and ignorance.

“The Treaties put us as equals, two nations who agreed to share the land and the resources, but it's easier to blame Indigenous people for –°¿∂ ”∆µ 'lazy' and 'drunken' than actually fulfill the Treaties, allowing us to heal from all the oppression, brutalization and killings allowed in the name of colonization.”

What needs to change

After the murder of Allan Thomas in 1963, the North Battleford News-Optimist wrote that CBC public affairs series Other Voices, did a documentary about the life of Indigenous people around the North Battleford region. They said CBC was prompted to do the piece after Maclean’s magazine compared the North Battleford region and its racial problems with the American south.

Today, Allan Thomas’ murder continues to shine a spotlight on the systemic issues that persist within the Canadian justice system.

“We believe the answer comes with better representation of First Nations amongst staff and within leadership at all levels throughout the Justice System,” Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations Vice Chief Edward Lerat, told SASKTODAY.ca. “Self-administered policing is also essential for the advancement of healing and reconciliation for First Nations.”

Kim Beaudin, National Vice Chief for Congress of Aboriginal Peoples, said Indigenous people have been dehumanized and he believes racism is worse in Saskatchewan, closely followed by Manitoba and Alberta. An added issue he said, is that newcomers to Canada are also taught to be racist against the Indigenous.

“People from other countries come here and are taught to hate Indigenous people from the get-go. That is a fact and that is a big problem.”

He’s not optimistic things will change anytime soon.

“Not in my life. It’s going to take a while.”

He said change starts with the colonial leadership at not just the national level but also provincial and municipal levels.

“They’ve done a really poor job of bridging the gap,” said Beaudin. “If our leaders don’t want to do the right thing maybe the community should be doing the right thing.”

Eleanore Sunchild said open dialogue and education are needed.

“We need to have frank and honest conversations about the true history of this country and admit the stereotypes and racism that have been taught and passed on.

“Indigenous people need compassion and understanding as we see the effects of racist colonial practices such as the Indian Residential School system, 60s scoop and the Indian Day Schools,” she added. “People have no idea about the level of trauma most Indigenous people went through in this province and these racist institutions continued well into the late 1990s. Our jails are full of survivors and inter-generational survivors and I think people need to think about that.”

Sunchild, however, remains optimistic that there will be change.

“I think the younger generations will be more open to learning about each other and improving relations.”

Note: Initial media reports had spelled Thomas’ name as Allen Thomas. Court documents, however, reveal that the correct spelling is Allan Thomas. Also, the term "Indian" is used only when quoting people directly.

This story was first published May 11,2023, by SASKTODAY.ca.

— for more from Crime, Cops and Court.