YORKTON - The Chicago Blackhawks are one of the most fabled teams in the NHL, but the history of the early years is less known than at least author Paul R. Greenland thought it should be.

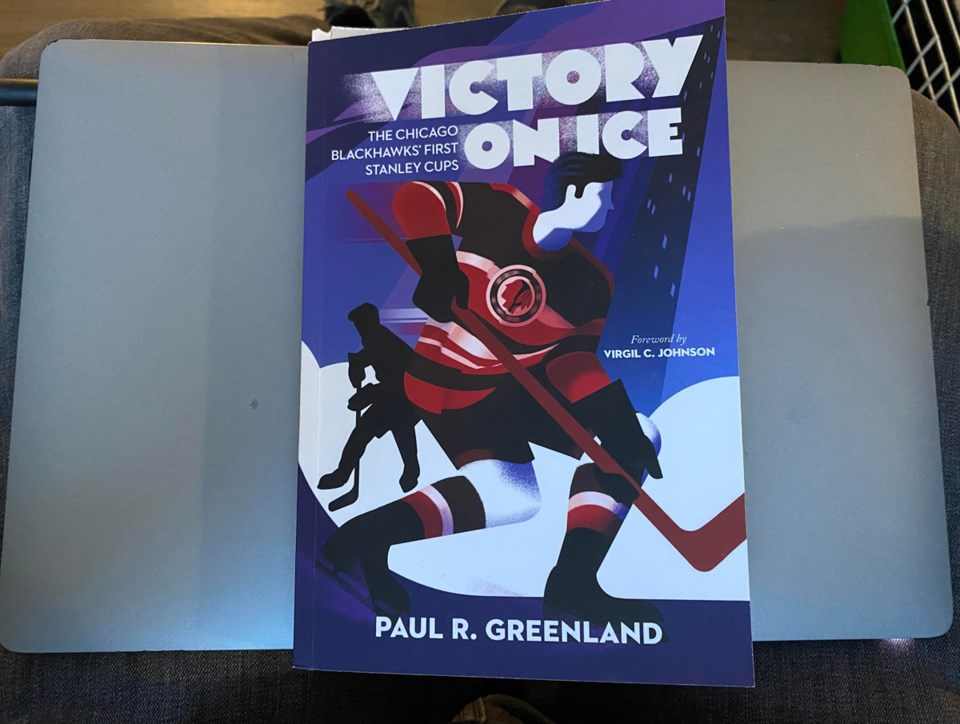

“Most committed followers know the Blackhawks won the Stanley Cups in 1934 and 1938, but these milestones, which happened a very long time ago – well before the “dynasty” – are seldom discussed and often overlooked,” he wrote in the introduction to his recent book; Victory On Ice.

“On April 14, 1994, the Blackhawks played their very last regular season game at Chicago Stadium. The cover of that night’s 72-page souvenir game program carried a tagline, “Remember the Roar,” in honor of the legendary arena. A full-page photo of the 1960-61 Stanley Cup team appears midway through the book, along with tributes to legends Tony Esposito, Glenn Hall, Bobby Hull, and Stan Mikita. An entire page is devoted to Al Second, but photos of the 1933-43 and 1937-38 Stanley Cup teams are missing.

“Their absence is unfortunate, because these early championship teams initiated the “roar” that fans were 小蓝视频 encouraged to remember. Long before Tony “O” and Mr. Goalie made their marks as puck stoppers and the Golden Jet and Stosh became scoring legends, an earlier generation of players electrified Stadium crowds. Chicago’s early hockey milestones were attained by players who were the superstars of their day. Many were pioneers, and some were enshrined in the Hockey Hall of Fame, the United States Hockey Hall of Fame, and numerous Canadian provincial halls of fame.”

As a native of Rockford, Ill., about 90 miles west of Chicago, Greenland undertook to uncover more of the lost history on the Blackhawks earliest Stanley Cup wins.

“The inspiration for this, when this journey all started, I didn’t see a game in person until I was 18,” he said, adding that game cemented his love of the team.

Seated in the ‘nose bleeds’ well above the ice, Greenland said he felt as though a slight push would send him to the ice far below.

But, he didn’t have long to worry about a push as a brawl between the Blackhawks and visiting Minnesota North Stars broke out pre game.

The fisticuffs extended quickly to the crowd.

“I had a beer poured all over me from behind,” said Greenland.

Fights were breaking out among fans.

Police were on the ice to restore order.

It was at the time a friend looked over and welcomed Greenland to ‘the stadium’ which he noted on that night certainly “lived up to its reputation as the ‘Madhouse On Madison’.”

“There was blood everywhere and equipment all over.”

While a different game from today, Greenland said the stadium was alive that night.

“The electricity in that old arena, if you missed it, you weren’t alive,” he said, later adding the new Hawks home “. . . Is a nice place but it doesn’t have the soul.”

A year later, at age 19, Greenland said, “I knew I was going to write a history of the team.”

He soon began pestering the team for help.

“I bothered the Blackhawks every day for a year before they finally invited me to a practice,” said Greenland, adding they agreed to meet after about his project.

Greenland would arrive 45-minutes early for the practice, sitting in the still dark stadium alone.

“It was the coolest experience . . . Just soaking up the atmosphere,” he said.

Over time Greenland would amass a mound of material, creating initially a tome of 100,000 words covering a broad canvas of Blackhawks history, which was eventually focused down to the team’s first two cups becoming Victory On Ice.

The material for a book on an era of hockey now almost a century in the past was a challenge.

“You’re trying to recreate a landscape from nearly 100 years ago . . . Working on a project like this requires some intestinal fortitude,” said Greenland.

Greenland said he was fortunate to actually get to know Harold ‘Much’ Marsh, and Carl ‘Cully’ Dahlstrom who both played with the team.

Marsh was from Silton, Sask., and played with the Blackhawks from 1928-29 through to 1944-45, while Dahlstrom was American born with the team from 1937-38 to 1944-45.

An interesting tidbit on Saskatchewan-born Marsh in the book is he “was the first player to score a goal in Toronto’s Maple Leaf Gardens on November 12, 1931. When the final game was played in the arena on February 12, 1999, March and former Maple Leafs opponent Red Horner participated in a ceremonial puck drop. Making the occasion special was the fact that March used the actual ‘first goal’ puck from 1931, a keepsake that was still in his possession.”

The Internet helped connect the author to the families of other players, and he said they were gracious in providing access to scrapbooks, telegrams and letters, a trove of personal accounts of the two cup winning runs.

Then it was into the files – many now online – of old newspapers which were the key way fans followed the game in the 1930s with the Internet and even television unknown, and radio still relatively new, Greenland explained.

But even with varied sources the book might not always be 100 per cent as it happened.

“It’s kind of like a puzzle,” said Greenland, adding while you try to fill in all the spots “. . . you’re never going to find all the pieces.”

Now complete Greenland just hopes a book on a long ago era for the Blackhawk resonates with fans today.

“I’m really, really hoping that a younger audience . . . are going to discover it,” he said, adding the history of the Chicago Blackhawks goes back long before the likes of Patrick Kane and Jonathan Toews, or even Bobby Hull and Stan Mikita to the likes of Marsh, Dahlstrom and Mike Karakas and the book is their story.