YORKTON - In the world of sport, one of the eras which both interests and saddens for this writer is the age of Negro League Baseball.

Certainly some of the greatest players in the game toiled in the leagues from the 1920s though the later 1940s – the likes of Josh Gibson, Satchel Paige and Cool Papa Bell, which makes the era intensely interesting.

But, there is sadness in the recognition such players were not allowed to play in the major league alongside white players. It was a time of ingrained racism, and while now a century in the past, the underlying issue of hated based on the colour of one’s skin is far from eliminated in our world.

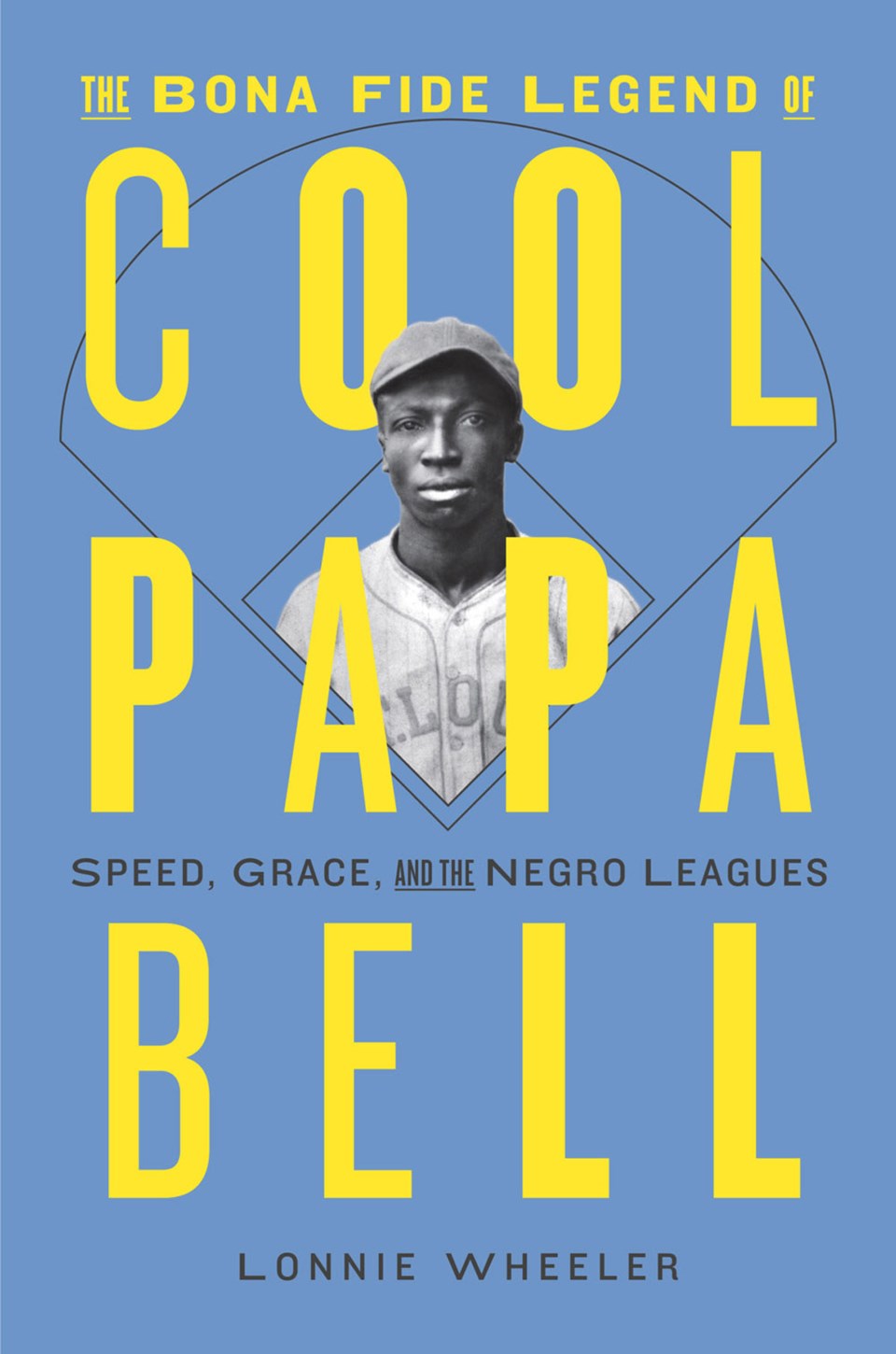

So when I cracked The Bona Fide Legend of Cool Papa Bell: Speed, Grace, and the Negro Leagues by Lonnie Wheeler, the racism Bell faced was the most compelling part of the book, although the book did seem to avoid the worst of it. I suspect that is because many players would have hesitated to talk of the hardships – much as veterans of war often kept the worst of the trenches on World War or time in POW camps bottled inside.

And, obviously the press of the day wasn’t going to write about the racism of the era either. It was a decidedly different time as the book notes with a single line; “In Atlanta, black and white baseball teams were not permitted to play within two blocks of each other.”

Typically, I would have asked Wheeler about it, but sadly he died before an interview was possible.

Still, the book, released in early 2021 by Harry N. Abrams, is still a fine read providing insights into a player who was elite in the sport of baseball.

“Over his double-digit years of playing periodically against major leaguers, it’s estimated that Bell batted .391 in those games,” wrote Wheeler. “That doesn’t include his .366 in a dozen seasons of California Winter League competition. Nor do those lofty numbers take into account Bell’s most distinctive contributions. When distinguished Courier writer Wendell Smith interviewed various Pittsburgh Pirates about their impressions of Negro League counterparts who worked in the same city, none mentioned Cool Papa’s batting average. It was merely incidental. “I have seen him score from second on just an ordinary fly to the outfield,” said Bill Brubaker, an infielder whose best season happened to be 1936. “He musta had wings on his feet. Bell was a big leaguer if there ever was one.” “Bell was one of the fastest men baseball has ever known, and he was a constant worry whenever he got on base,” asserted Pie Traynor, the Bucs’ manager and Hall of Fame third baseman. “He’d steal a pitcher’s pants. I always admired him for his dashing spirit and ability to get the jump on opposing pitchers. And he could go a country mile for a ball. He could have made the grade easily.”

But, in the end the greatness of Bell and his contemporaries which shines through this book, still pales when one reads of the racism.

“In any event, the Crawfords found their spring road swing to be more challenging socially than athletically. When the team bus parked Oscar Charleston didn’t look so mean when posing with his wife, Jane at a restaurant in Picayune, Mississippi, for example, folks inside came out to ask if there were any white people on board. Hearing there weren’t, they advised that the ballplayers best be moving along before the law showed up and put them all to work on the county farm with the coloreds who had tried to pass through previously,” wrote Wheeler. “In another small town a local stalwart pulled a shotgun on Paige and Johnson for the indiscretion of dressing in too highfalutin a fashion. In Arkansas, with Cool Papa kneeling on deck, a fan threw a chair onto the field . . .

“A subtler incident, some years later in rural Kentucky, disturbed Cool Papa more profoundly. The players drove up to a gas station, spotted a well behind it, and asked the lady in charge if they might indulge in drinks of water. There was a gourd hanging from the side of the well for that purpose. She consented, they drank and thanked her, and as they drove off Bell was sickened by the sight of the woman smashing the gourd to smithereens against the side of the well.”

That image doesn’t leave much for this writer to say, other than to read the book for insights into the great Bell, and for lessons yet to be fully learned regarding the insidiousness of racism.