YORKTON - The 50th anniversary of an event only comes around once, and when it is arguably marking the greatest sports event in a country’s history, scribes are likely to take the opportunity to chronicle the history in book form.

And so it has been this year in Canada as the ’72 Summit Series between this country and Russia in Hockey marks the anniversary.

A number of books have been released on the series, a couple previously written of here; Ice War Diplomat by Gary Smith and 1972: The Series That Changed Hockey Forever by Scott Morrison, and now we look at a third title on the subject.

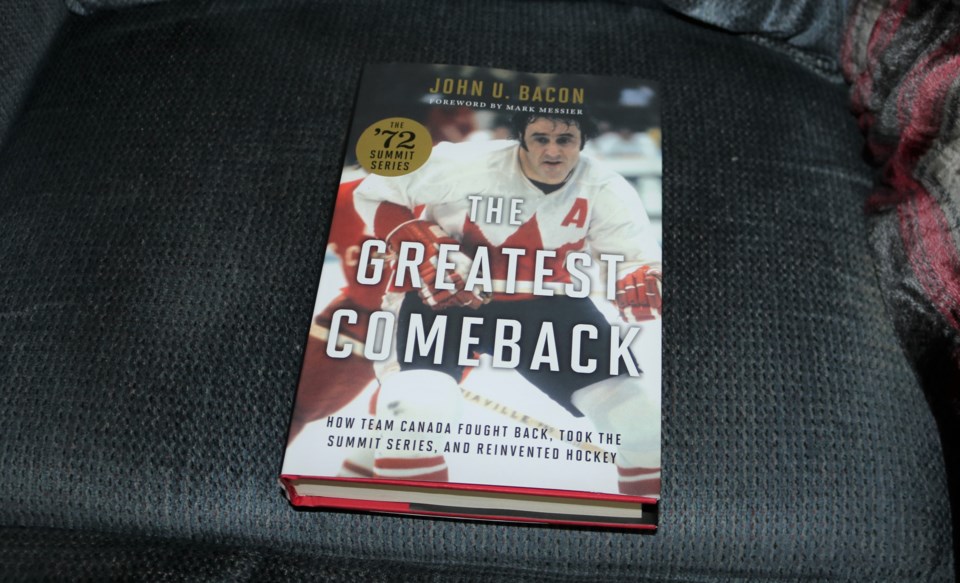

The Greatest Comeback: How Team Canada Fought Back, Took the Summit Series, and Reinvented Hockey is John U. Bacon’s contribution to looking back at the fabled series.

Of course this was a story that was never suppose to have the drama it turned out to have, as Bacon noted in his introduction.

“Team Canada opened the Summit Series as one of the most heavily favoured teams not merely in the history of hockey, but in the history of sports.

“Just about every Canadian fan, journalist, player and coach expected the greatest hockey team ever assembled to crush its untested opponents, eight games to zero. Team Canada’s leaders were so certain of victory that they invited 35 players, two full teams’ worth, to their training camp in Toronto, and promised all of them that they would get into at least one game. Anticipating little competition from the Soviets, they figured they could use the older players for the first four games in Canada, then let the younger players mop up the last four games in Moscow.

“But that, of course, is not how it went,” he wrote.

So when Bacon was approached to write the new book it was too good an opportunity to pass up.

“It was the last chance to tell the story fresh,” he said.

It was the access to players that Bacon said gives his book fresh insights.

“The value of my book is they asked me to do it,” he said, adding that allowed him to interview the likes of Bobby Clarke and Phil Esposito and others, mining their memories for fresh insights into the series.

Of course with such access Bacon said he keenly felt a responsibility to tell the story well on behalf of the players.

Still, is Bacon surprised the series still draws the level of interest that it does?

“At the time it happened we knew it became a much bigger thing that we expected,” he said.

For those who might not know about the series; “The Summit Series took place in September 1972, when Cold War tensions could not have been higher,” details the publisher’s page at . “But that was the whole point of setting up this unprecedented hockey series. Team Canada, featuring the country’s best players—all NHL stars, half of them future Hall of Famers—would play an eight-game series, with four games played across Canada followed by four in Moscow. Team Canada was expected to crush their untried opponents eight games to zero, with backups playing the last four games.

“But five games into the series, they had mustered only one win against a tie and three stunning losses. With just three games left, Team Canada had to win all three in Moscow—all while overcoming the years of animosity and mistrust for one another fostered during the Original Six era. They would also have to overcome the ridiculous Russian refereeing that resulted in stick-swinging fights involving the players, a Canadian agent and Soviet soldiers; surmount every obstacle the Soviets and even the KGB could throw at the players and their wives; invent a hybrid style of play combining the best of East and West, one that would change the sport more than any other factor before or since; and win all three games in the last minute.

The series resonated across the nation.

When Paul Henderson scored in the last minutes of game eight to salvage a series win for Canada, a hero was born, a nation cheered, and history was assured.

“Foster Hewitt made the call: “Henderson had scored for Canada!”,” wrote Bacon.

“Not just “scores,” or even “scores for Team Canada.” But for Canada, the country, and all its native sons and daughters. And they were all watching. When Gretzky and Messier constantly refer to Team Canada as “we,” though they were just 11-year-old kids watching, that tells you what the team meant to the country. By Game Eight, Team Canada was the country.”

Bacon said players understood the importance even more when they flew back to Canada after the historic series and found out “the whole country had shut down” watching the pivotal games from Moscow.

And, 50 years later, Bacon said he sort of expected a lot of attention to the anniversary, including the many books.

That said, the interest from younger people was less anticipated.

“I’m surprised . . . by people in their 30s – their parents hadn’t met yet (in 1972) –who are interested,” he said, adding it is further testament to just how unique the series really was.

“It was the most unifying moment is Canadian history,” offered Bacon.

Yes, there was confederation itself, but that was a slow process over many years, and the two world wars, but those where a shared experience with Canada’s allies, so the Summit Series stands out.

“This is Canada’s alone,” said Bacon, adding for eight nights in 1972 every Canadian was aware of the series. “. . . It brought Canada together more than anything before, or since . . . Name another moment when every Canadian knew exactly where they were. It was bigger than hockey – no question.”

Of course it was also about the game, the one Canada has always held dearest too.

“Canada is the only country where the top sports, one, two and three are ice hockey,” noted Bacon.

While Canadians are naturally humble in most things, that changes when dealing with hockey. Bacon said we are prideful when it comes to our beloved sport, and that showed in 1972 as the series played out, and still shows with the interest remaining in the series 50-years later.

Mark Messier noted the pride in his foreword to the book, and it seems a fitting excerpt to end with.

“The whole thing was just an incredible display of pride and grit and determination. Not only to come back again and again and again, but to finish the job the way they did. The Canadian pride was in full bloom. I had uncles who were in the air force, and we’d all heard stories about World War II. I know this wasn’t war, but this was as close as we would get. To see it live, to feel it, to see your heroes, and this incredible effort fighting for Canadian pride – an unapologetic pride, so rare for us – we will never forget it. This was the first time kids my age really felt the full magnitude of Canadian pride,” he wrote.